Past crises have taught the microfinance sector a lot about weathering storms. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are once again facing challenging times. This case study is part of a series that CFI, in partnership with the European Microfinance Platform (e-MFP) and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, is publishing to (re)visit tales of tough times and resiliency in five markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nicaragua and Palestine – and discuss how MFIs, with the help of their investors and other stakeholders, emerged and thrived. The lessons learned from these cases will be compiled and examined in a forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, a follow up to the first edition published in the aftermath of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The hope is that these lessons will be applicable to not only the COVID-19 response, but to future crisis responses as well.

Aynur Aliyeva began 2015 in limbo and facing uncertainty. Her CEO had just left Azerbaijan and gone back to the Philippines, thousands of miles away, having been denied a renewed work visa a few months earlier. As his deputy at the Azerbaijani microfinance company Viator, Aliyeva stepped in, working feverishly with lawyers and government authorities to bring the CEO back. Unbeknownst to her, a far greater challenge loomed just ahead.

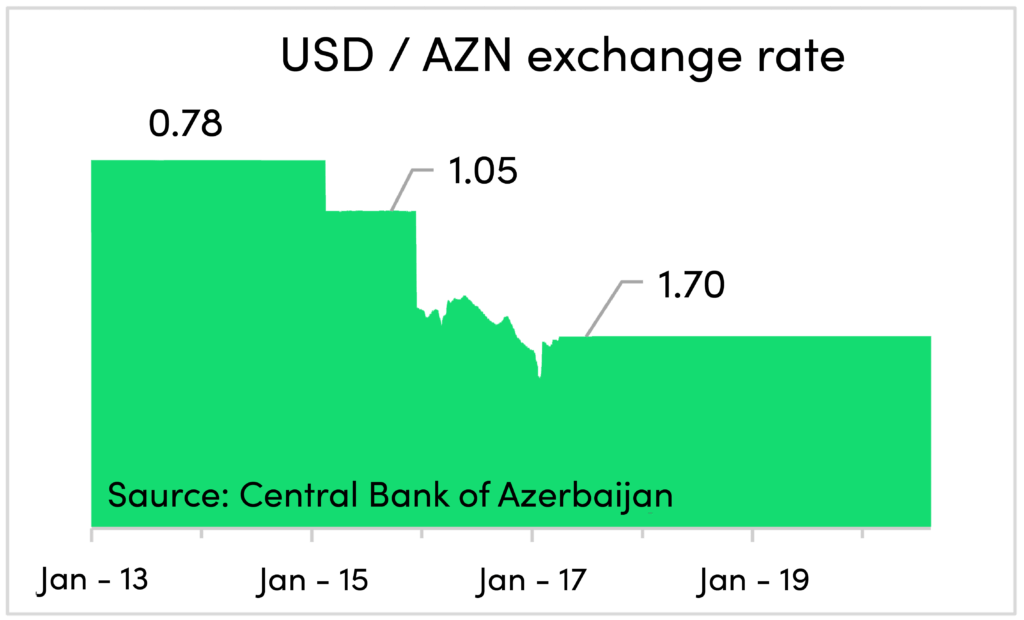

On February 21st of that year, the Azerbaijani currency, the manat, lost 25 percent of its value — all in a single day. For a country whose currency had been steady since at least 2000, even during the height of the global financial crisis in 2008-09, such a devaluation was a major shock. It capped a year of severe economic pressures, with falling oil prices over the past year having already been felt in every corner of the petroleum-driven economy. Even with that, the devaluation was something new entirely — “snow in the middle of summer,” thought Aliyeva.

These pressures were bearing down on Viator. Like other MFIs in the country, much of Viator’s portfolio was lent out in USD-denominated loans, and most of its debt was likewise in dollars. Now its borrowers — few of whom actually earned USD incomes — were facing large payment shocks, on top of already being affected by the slowing economy. Viator was entering an existential crisis. Meanwhile, Aliyeva spent those initial few months navigating between a remote CEO, concerned investors and staff, and a loan portfolio that was fast deteriorating.

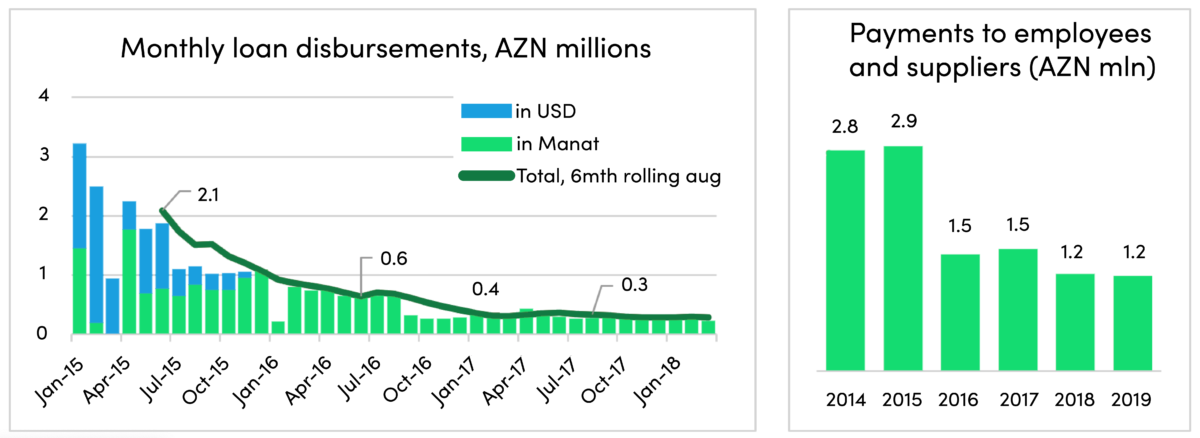

In April 2015, Aliyeva was finally appointed CEO. With that uncertainty resolved, Viator embarked on a crisis response. Its first step was to change its lending policy; until then, Viator had been lending between a third and half of its loans in USD. With the devaluation, it began to sharply curtail this practice, bringing USD disbursements down to zero by the end of the year. That was just in time, because on December 21st, the manat was suddenly devalued again, this time by another 32 percent. With these two devaluations, the manat had lost half of its value — and the decline would continue through 2016 into 2017.

The resulting fear and uncertainty, combined with a major recession, destroyed trust and threw the entire financial sector into turmoil. Viator was a small fish, had no deposits, and certainly did not meet the too-big-to-fail test. Its primary shareholder was a Norwegian NGO that, while morally supportive, had little financial expertise and no access to additional capital. If Viator was to survive, it would have to do it on its own.

And survival was indeed at stake. Several of the country’s MFIs, far larger and more important than Viator, would not make it.

Aliyeva had never run an MFI in the midst of crisis, but that had its advantages, too — she carried no “founder’s syndrome” baggage; whatever mistakes were made previously were made by her predecessor. This allowed her to ignore the past and focus entirely on the present and the future.

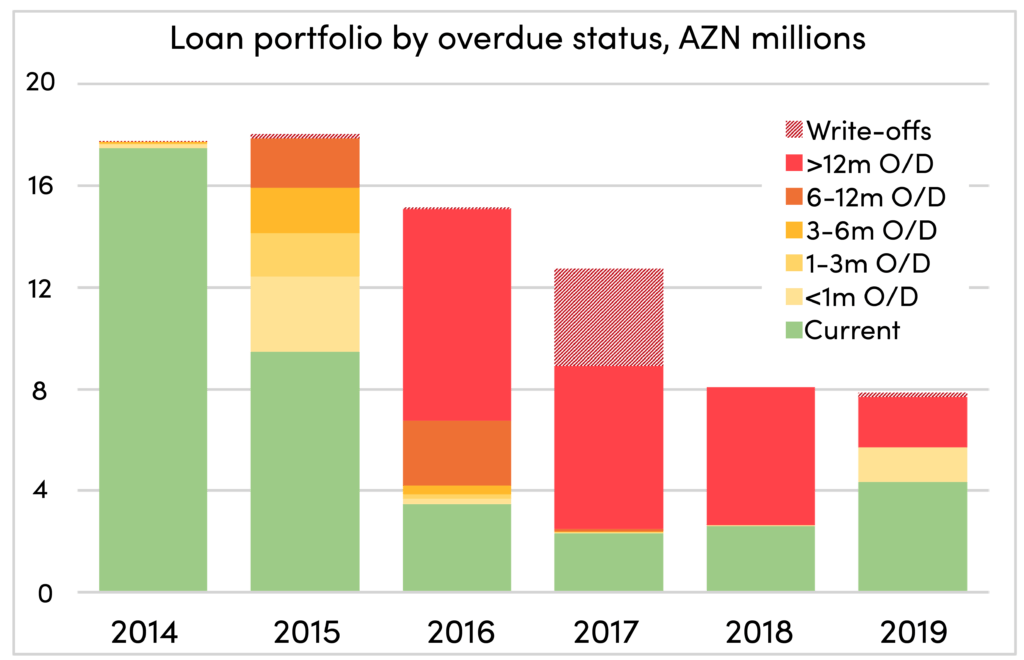

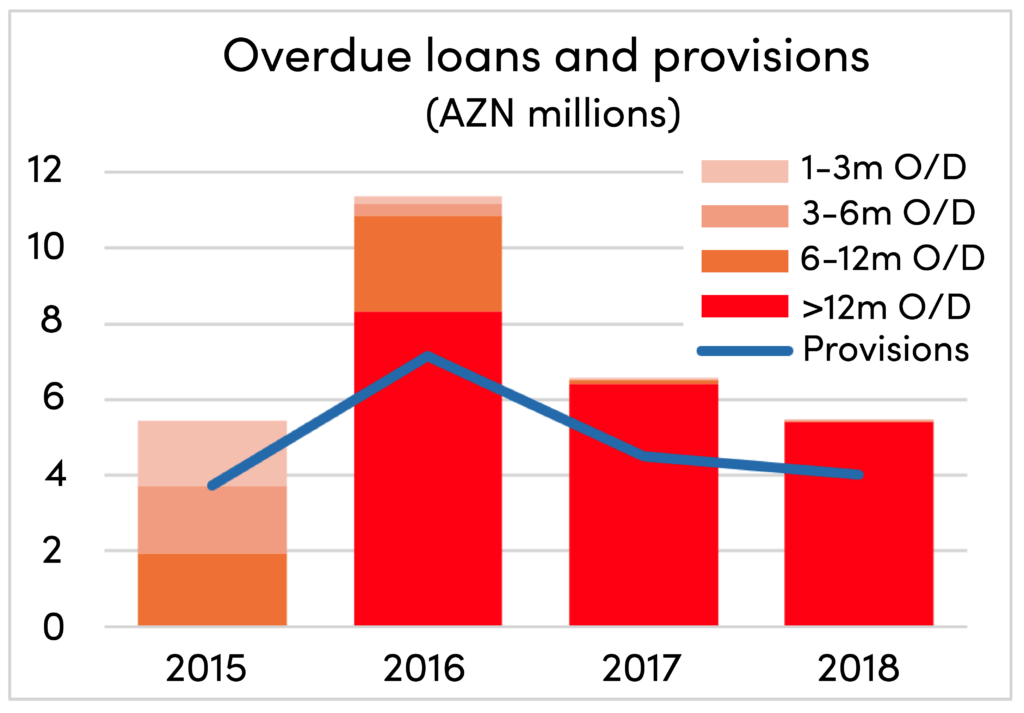

In the meantime, in Viator’s portfolio, things were going from bad to worse. By the end of 2015, 47 percent of its loans were overdue. A year later, that number had grown to 77 percent, comprising mostly loans that were by then more than 12 months behind. Faced with such numbers, most managers would panic.

Aliyeva did not panic. With many of the country’s financial institutions — banks and MFIs alike — hunkering down in the midst of crisis, Viator suddenly found a wide-open market. In the face of uncertainty and volatile cash flows, people still needed to borrow. And so Viator continued to lend. Indeed, no matter how bad things got during the long crisis period, Viator never stopped lending.

Having already switched to entirely local currency loans, Viator focused on the best clients and low-risk products. Chief among these was the jewelry loan, which allowed clients to monetize the gold received during weddings and other family events — a common cultural practice in Azerbaijan. With this secure and relatively liquid collateral, Viator could lend during the depths of the crisis, and still keep credit risk low.

Of course, this new lending was far below pre-crisis levels. Midway through 2016, monthly disbursements averaged AZN 0.6 million, or 70 percent lower than a year earlier. By mid-2017, this was cut again by half, down 83 percent from the level set two years before. These lower disbursements were accompanied by lower operating costs; in 2016 alone, operating expenses were halved, mainly through salary cuts and staff attrition, as well as layoffs that prioritized retention of the best-performing and most experienced staff.

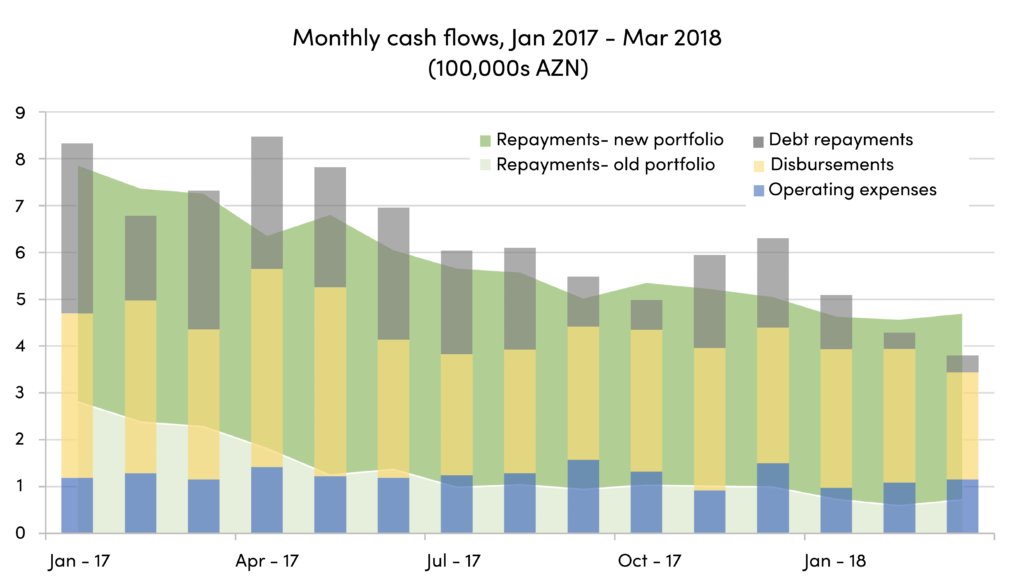

Though shrinking, Viator was by no means closing its doors. Despite the greatly reduced levels, new disbursements proved crucial to its survival. By January 2017 — a year after the second devaluation that marked the full onset of the crisis — repayments from its new portfolio of jewelry-backed loans accounted for nearly two-thirds of Viator’s total cash inflows. Indeed, for nearly five years during the period 2015-2019, loan repayments were Viator’s sole source of cash inflows. That proved crucial not only for allowing Viator to continue disbursing new loans, but also to continue to repay its debt.

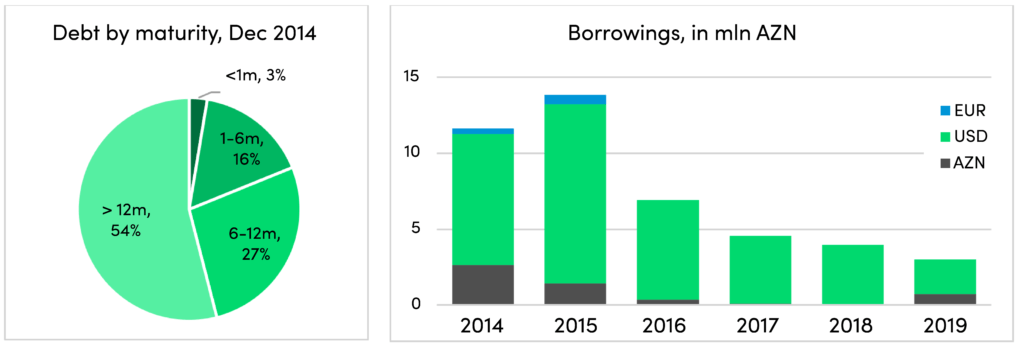

At the start of 2015, nearly all of Viator’s funding was in the form of debt from foreign social investment funds, mostly in foreign currency. Given the depth of the crisis, its investors were naturally worried. Many had also invested in other MFIs in Azerbaijan, not surprising considering that just before the crisis, the country was one of the five largest markets in the world for microfinance investment. Now these investors were faced with preserving capital and minimizing losses.

Complicating matters further, some investors had disbursed their investments as recently as February 2015, while others were already near the end of their loan maturities. With Viator in violation of multiple debt covenants, investors faced the same coordination problem that arises with nearly every crisis-stricken MFI: if all of them were to follow the loan covenants and accelerate their debts, they would be fighting for the meager leftovers of a liquidated entity. Not only would they face steep financial losses, they would also be abandoning an MFI that was one of the few institutions still providing loans to excluded rural households in Azerbaijan.

To nearly all investors, the answer was clear: the debt had to be restructured. Despite this, the negotiations among them proved challenging. Some of the investors had prior experience handling workouts, but for others, this was the first time. There were additional obstacles that some negotiators faced when needing to explain these inter-creditor discussions and tentative agreements to their own credit committees, some of which had limited experience investing in microfinance or even in emerging markets more generally. For one credit committee, the sole reference point for debt restructuring was a court-supervised process — a drawn-out and deeply uncertain option in the context of Azerbaijan. Educating them in these realities took time.

One crucial input into these negotiations was an assessment and recommendations from an external advisor, hired by Viator in early 2016 upon the recommendation of one of its investors. The advisor had extensive experience managing situations such as this, having worked at a crisis-stricken MFI in Bosnia and Herzegovina during its turnaround following the 2008 crash. Her report found that while Viator was deeply affected by the crisis, its operations were sound and it remained a viable institution that could survive the crisis. The report also contained a series of suggestions to Viator, especially aimed at strengthening collections on overdue loans — advice that Aliyeva readily adopted.

The consultant went further and invited several of Viator’s senior staff to her former MFI in Bosnia to directly observe the collections systems the MFI had instituted during its turnaround. This experience, along with training of Viator’s collections staff, were crucial factors into Viator’s crisis response.

The work this consultant did for Viator was not only important to the MFI; included with her report was a series of cash flow projections that showed the turnaround to be very much possible. These projections would prove a critical input for Viator’s investors.

Throughout this time, Viator’s transparency and openness with both the external advisor and with its investors played an important role in building trust. As it happens, several of the fund managers had also invested in another Azerbaijan MFI that took an approach that was diametrically opposite from Viator’s. Its unwillingness to communicate and share information made Viator’s openness even more notable in the investors’ eyes — and made them more willing to make the difficult decisions required for the workout.

Viator’s transparency and openness with both the external advisor and with its investors played an important role in building trust.

With the consultant’s report concluded in June 2016, negotiations among Viator’s creditors swung into high gear, and finally in August 2016, they signed an inter-creditor agreement that extended all loans, regardless of maturity. The agreement specified a single repayment schedule for all investors, who would be paid pro rata, but using a formula that gave some additional preference to debts with the earliest maturities. The agreement also fixed a discounted interest rate of 5 percent for all creditors. Over the course of the next two years, reflecting the depth of the crisis, this agreement would be amended twice more, adding further discounts to the interest rate.

During these negotiations, Aliyeva was adamant that rather than funneling all excess inflows from loan repayments back to its creditors, Viator should use a substantial portion of these cash flows in order to reinvest in new lending. For investors, this meant they would have to sacrifice some repayments in the short-term. It is here that the external consultant’s projections proved crucial, for they showed the value of reinvesting cash flows into new loan disbursements. Indeed, a number of Viator’s investors used these same projections as a benchmark to monitor Viator’s performance over the coming months.

With its liquidity thus stabilized, Viator could focus on managing its solvency situation. Here, things were arguably even more challenging. It certainly helped that Viator entered the crisis well-capitalized, with equity comprising 40 percent of total assets at the end of 2014. Even so, that generous level of capital was not enough when 63 percent of its pre-crisis portfolio was six or more months delinquent by the end of 2016. One way that Viator handled this challenge was by adapting its provisioning practices. At the outset of the crisis in 2015, it provisioned generously (100 percent for all loans overdue by more than 90 days), in 2016-18 provisioning dropped to as low as 64 percent, even when nearly all overdue loans had by then exceeded 12 months.

The decision to change its provisioning rules helped conserve much needed equity, which by 2017 had eroded to just 13 percent of assets. Doing so bought crucial respite during the years that non-performing loans continuing to fester on its books. Finally, rescue arrived in 2019, four years after the onset of the crisis, when the Azerbaijani government implemented a rescue package for the microfinance sector. Through it, Viator received both a grant and a subsidized loan from the Central Bank of Azerbaijan that allowed it to cover a major portion of its losses. Only then did Viator once again fully provision for its delinquent portfolio. Almost exactly five years after the onset of the crisis in February 2015, Viator could finally close the last page on this difficult episode and truly look forward.

A few months later, it was facing COVID-19…

What are some dos and don’ts and key factors of success that the microfinance sector can learn from the Viator case? CFI’s forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, will draw on lessons from this case and cases from microfinance institutions in four other markets – Bosnia and Herzegovenia, India, Palestine and Nicaragua. See also CFI’s original Weathering the Storm report from 2011.