Past crises have taught the microfinance sector a lot about weathering storms. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are once again facing challenging times. This case study is part of a series that CFI, in partnership with the European Microfinance Platform (e-MFP) and the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth, is publishing to (re)visit tales of tough times and resiliency in five markets – Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, India, Nicaragua, and Palestine – and discuss how MFIs, with the help of their investors and other stakeholders, emerged and thrived. The lessons learned from these cases will be compiled and examined in a forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, a follow-up to the first edition published in the aftermath of the global financial crisis a decade ago. The hope is that these lessons will apply to not only the COVID-19 response, but to future crisis responses as well.

By the time the world awakened to the severity of the 2008 financial crisis, the damage to the global economy was evident. Earlier that year, the Nicaraguan economy, then dominated by agriculture, contracted dramatically as export demand plummeted. Tens of thousands of farmers found themselves unable to sell their products, their basic livelihoods threatened. The economic contraction was felt by many of the clients of Nicaraguan MFIs, many of whom had taken out loans to prepare for the growing season.

Before the recession, credit had flowed freely throughout the country thanks to international investors looking for new investment opportunities. Although cheap credit at the time was helping to drive consumption and production, Victor Tellería, the CEO of Financiera FAMA, a regulated MFI, knew it was only a matter of time before the recession would be felt in Nicaragua.

As MFIs soon realized, thousands of their clients found themselves unable to repay debt. Not only did the recession lead to many MFI clients being unable to meet debt obligations, it also brought to light concerning practices of some institutions in the Nicaraguan microfinance industry. Some of the most blatant abuses included hidden microloan fees, forced savings in the form of compensatory balances, and very high late-payment charges. Tellería had also heard reports of some borrowers who had taken on debt in the upwards of thousands of dollars, usually from multiple MFIs, which was of particular concern given the average GDP per capita in Nicaragua was around $1,500. The result of these socioeconomic conditions and lending malpractices triggered the rise of the No Pago (Don’t Pay) movement (NPM) in 2008 – a movement that would challenge MFIs throughout Nicaragua.

The “No Pago” Movement

Originating in the northern state of Nueva Segovia at the beginning of 2008, the NPM, supported mostly by farmers with outstanding loans under judicial recovery processes, called for the non-payment of loans. With the backing of some sympathetic members of the National Assembly, NPM leaders lobbied the government for legislation to put a moratorium on all debt payments nationwide. Eventually, a settlement was reached: MFIs agreed to renegotiate and restructure all delinquent debt instead. FAMA was the only regulated MFI that participated in negotiations with the leaders of the NPM, even though it did not have a strong presence in the region impacted by the NPM.

Despite the agreement reached between MFIs and their clients, the NPM quickly turned violent. The Nicaraguan president urged the protesters not only to stop paying and demand renegotiation on their loans, but to move their protests to local MFI branches. The NPM’s most violent moment came in July 2008, when, shortly after the president’s comments, the movement temporarily kidnapped staff at some MFIs and attempted to burn down the offices of one of FAMA’s competitors in the city of Ocotal. The governmental support for non-payment of loans led international impact lenders, which constituted the bulk of the MFI industry’s financing, to reduce their support for MFIs in Nicaragua.

The No Pago Movement and the global recession created a perfect storm.

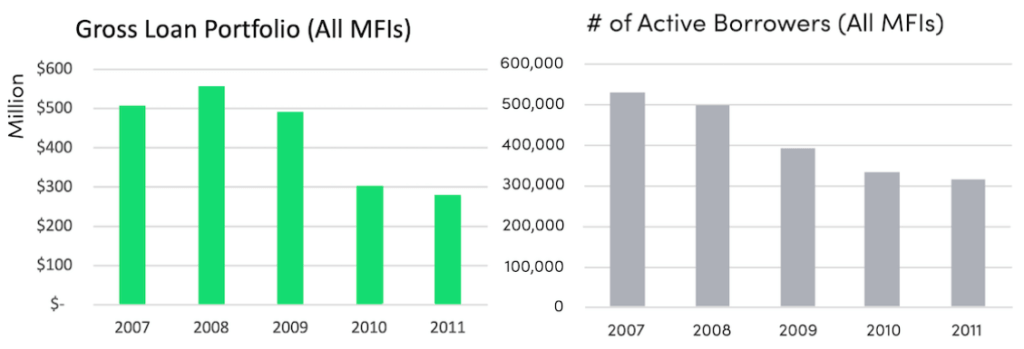

The No Pago Movement, coupled with the global recession, created a perfect storm that had a devastating impact on the microfinance industry throughout the country. Between 2009 and 2010, 19 microfinance institutions lost over $60 million in financing from international investors. The overall MFI credit portfolio at risk (portfolios at risk for more than 30 days) skyrocketed to close to 17 percent from an average of 3 percent before the NPM. Moreover, some MFIs went out of business or had to be heavily recapitalized, and the number of loans originated by microfinance institutions sharply decreased, resulting in more than 100,000 active MFI borrowers no longer receiving credit.

Regulation and New Policies

By late 2009, the NPM continued to petition the government for their demands. Further developments, including an embezzlement scandal at another MFI, only emboldened the movement. Continuing to believe they were being taken advantage of, the leaders of the NPM began pushing for legislation to establish a moratorium on all payments to MFIs. Within a few months, the Nicaraguan government passed the “Moratorium Law,” which took effect in April 2010. The Moratorium Law, which was criticized by the Microfinance Association of Nicaragua (ASOMIF) and investors, mandated that all MFIs renegotiate all past-due loans as of June 2009 and required all MFIs to suspend all legal recourse and asset seizures. The law also instituted an interest rate cap of 16 percent per annum on all renegotiated loans, much lower than the industry average of 33 percent.

Much of the Moratorium Law’s criticism stemmed from ASOMIF’s members who believed these new restrictions would institute a culture of non-payment, prevent good clients from receiving new loans, and discourage future investment in Nicaraguan MFIs. This legislation put the microfinance industry in a precarious situation as the industry had to adapt to stringent rules and regulations that did not provide a clear path forward for many MFIs to continue operations.

Finally, in 2011, after many deliberations, the National Assembly passed legislation to better regulate the microfinance sector. The legislation established the Comisión Nacional de Microfinanzas (CONAMI) as the regulatory body of microfinance to support the free negotiation of interest rates between MFIs and their clients, enforce consumer protection principles, and promote microfinance. All unregulated MFIs were required to register with CONAMI.

FAMA’s Road to Recovery

Founded in 1991, Fundación FAMA had served as a vital MFI for thousands of microenterprises, families, and entrepreneurs throughout Nicaragua. From inception, Tellería had overseen FAMA’s growth from a small NGO to one of Nicaragua’s largest MFIs. By 2006, Fundación FAMA decided to transition from a non-profit to a regulated financial service provider to the poor, otherwise known as Financiera FAMA. After officially becoming a regulated entity in 2007, Financiera FAMA was expecting 2008-09 to be their best year to date.

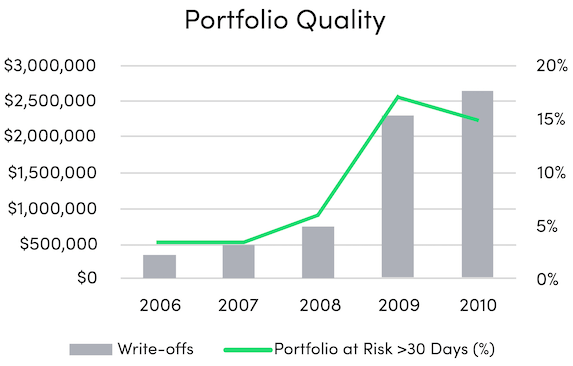

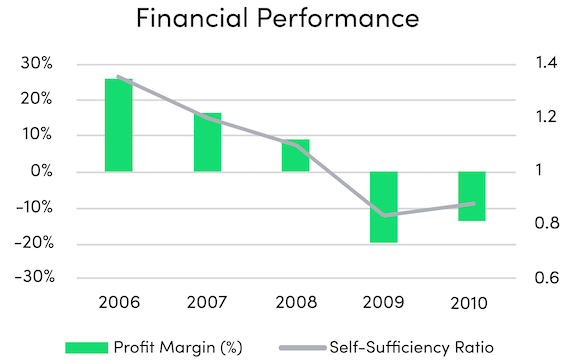

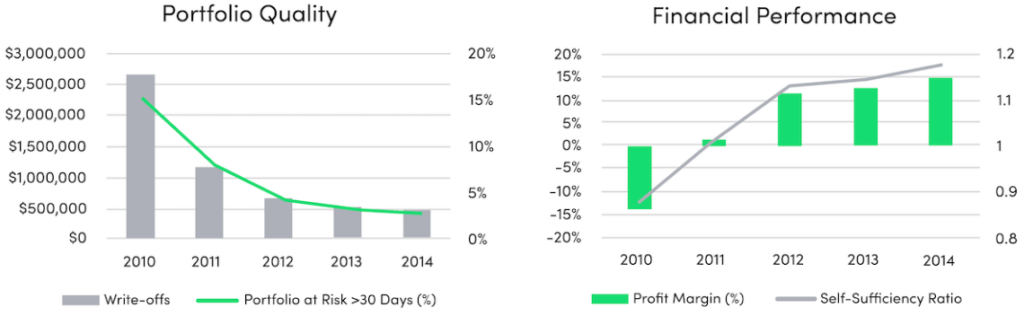

Before the recession, FAMA’s PAR>30 hovered around 3 percent, but had jumped to 17 percent by 2009 (see “Portfolio Quality”). Between 2009 and 2010, FAMA reported its first negative net operating income since it opened its doors. During that same period, FAMA’s balance sheet also shrank over 40 percent from $46.4 million to $25.8 million as the company wrote off $4.9 million in loans.

Furthermore, FAMA was no longer financially self-sufficient. Its self-sufficiency ratio, a measure of its ability to cover expenses and loan loss provisions with revenue alone, fell to .83 in 2009, meaning FAMA could no longer sustain its business operations without additional outside funding (see “Financial Performance”). Due to the lack of funding and an increase in past dues, FAMA lost 38 percent, or 17,000, of its active borrowers.

Recognizing how urgent the situation was, Tellería and his executive team needed to act quickly. At a critical September 2009 meeting of the board and FAMA’s lenders, many of whom had been with FAMA since the beginning, Tellería presented what FAMA needed to do to survive the crisis. There were two main areas that Tellería believed needing addressing: internal business operations and liquidity.

Operational Challenges

After intensive analysis, Tellería, his executive team, and a consulting team from Accion identified three main operational factors that needed to be addressed: high staff attrition, low compliance with policies, and increasingly large loans to clients outside of the microfinance sector, which resulted in the deterioration of FAMA’s portfolio quality.

Under FAMA’s operating model, the loan officer was responsible for all aspects of lending: loan sourcing, credit evaluation, and collections. In other words, the loan officer was both a credit analyst and a business development officer. This operating model put tremendous pressure on the officer to prioritize the quantity of sourcing new loans over the quality of those loans, which resulted in them taking shortcuts to boost their production numbers by performing superficial credit analysis, which, in turn, led to low portfolio quality. Furthermore, the staff attrition rate was high because if loan officers didn’t meet their loan goals and earn their expected commission, they would leave for a competitor institution.

The loan officer was both a credit analyst and a business development officer. This operating model put tremendous pressure on them.

To increase both the quality and quantity of microloan sourcing, the executive team proposed capping the maximum loan size and adding a second staff level to the loan process — a “promoter”– who would serve as the first line of customer service. Under the new model, the promoters would be paid a base salary plus a commission for new and renewal clients. To reduce the time it would take a promoter to refer a client to a loan officer for credit analysis, FAMA put mobile phones in the hands of the field staff and established a centralized call center. If the promoter had a potential new or returning client, they would message the officer with the client’s name along with their national ID number, who would then check the client’s credit history with the industry’s primary rating agency, Sin Riesgos (No Risks). After a few minutes, the loan officer could determine whether the client was creditworthy enough to be pre-approved for a loan within FAMA’s new loan cap and then move on to a more rigorous underwriting process.

Since the turnaround time on pre-approvals could now take just a few minutes, FAMA would require all promoters to meet specific outreach and customer engagement goals for both new and renewal clients. As a result of this change, loan officers would no longer be solely focused on lead generation and could instead prioritize their efforts to improve customer service, credit analysis, and client retention. To implement FAMA’s new business model, Tellería established a new centralized department, the “Methodology Supervision” department, to organize staff trainings and ensure staff adherence to lending policies. The trainings were organized by an international group of consultants from Accion to identify and eliminate any poor practices that may have impacted client experience and attitudes towards FAMA.

Loan officers would no longer be solely focused on lead generation and could instead prioritize their efforts to improve customer service, credit analysis, and client retention.

Liquidity

At the same September 2009 meeting, Tellería alerted the board that FAMA’s financial position was beginning to deteriorate due to the impact the recession and the NPM had on their operations. For Tellería to restructure FAMA’s business operations, he needed to find additional funding to cover any liquidity issues. As a result of Tellería’s new plan to address FAMA’s internal challenges, the deep experience of his board, and the commitment of his shareholders — along with FAMA’s position as one of the leaders of microfinance in the country — FAMA’s lenders generally continued their strong support for FAMA.

Because the need for funding was immediate, the lenders agreed that the best path forward would be to secure additional debt to offset any liquidity challenges as Tellería implemented FAMA’s strategic plan. Before the additional funding could be provided, the two lead investors — Accion and FMO — required that all FAMA’s current international lenders, except for three who wanted to exit Nicaragua, renew their loans with at least 24-month maturities.

Recognizing the need to reduce FAMA’s interest expenses, Fundación FAMA, who had remained the majority shareholder, also agreed to convert approximately $2.5 million debt into equity. In the end, Accion and FMO extended roughly $6 million in new credit to FAMA. Despite the challenges FAMA faced, it made every payment on time to all lenders, as originally contracted, and received renewals from most of them.

Coming Out of the Storm

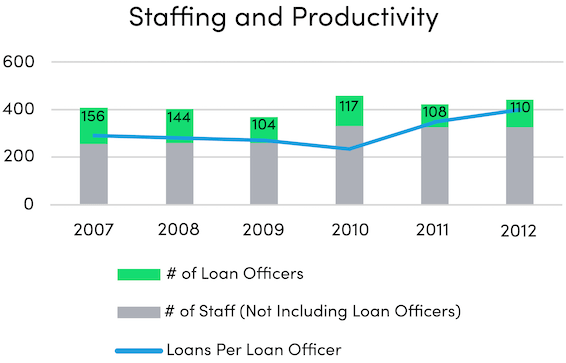

As a result of the internal business changes outlined in Tellería’s proposal, loan officers built larger, more resilient loan portfolios. By 2012, FAMA had increased the total number of loans per loan officer while decreasing the total number of loan officers needed in the field. PAR 30 and write-offs were also approaching FAMA’s pre-NPM numbers.

The team also analyzed their customer segments to understand the impact of NPM on the portfolio. After the assessment, Tellería noted that the microenterprise segment, FAMA’s largest customer segment, was the most resilient throughout and coming out of the NPM. The team also found that FAMA and many MFIs in the country had drifted upstream to provide increasingly larger loans to small and medium enterprises (SME), which was a nascent space for them.

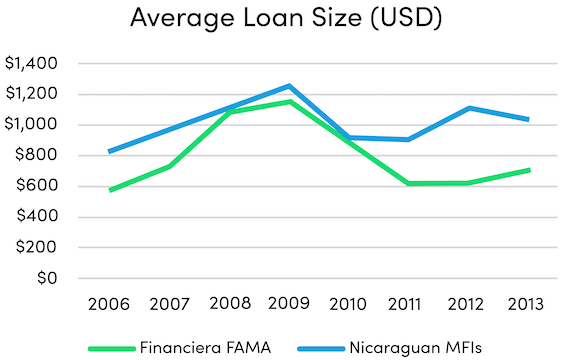

As it turned out, the SME sector was the MFI portfolio segment most negatively impacted by the global recession and the NPM. This issue, combined with a lack of credit discipline and decentralized operational support for the rapid expansion, was also key to FAMA’s under-performance. However, due to the changes to their business operations, FAMA quickly reduced its exposure to the SME sector by capping maximum loan sizes (see “Average Loan Size”). The decision to put a cap on loan sizes also helped FAMA refocus on its target demographic — low-income, underserved people — and ensure they continued to be served effectively.

The agreement made with lenders and the board, coupled with critical operational changes and technology investments, ensured FAMA’s mission to serve the poor would continue.

By 2013-14, FAMA was back to its pre-NPM financial and operational strength. Ultimately, the agreement made with lenders and the board, coupled with critical operational changes and technology investments, ensured FAMA’s mission to serve the poor would continue. In several subsequent meetings, the board and FAMA’s lenders have pointed to the joint support of Accion and FMO as paramount to allowing FAMA to remain the leading MFI in the Nicaraguan microfinance market. Ultimately, the loan agreement made with lenders and the board, Tellería’s strict adherence to servicing FAMA’s debt on time, and critical operational changes and technology investments, gave confidence to all parties that FAMA’s mission to serve the poor would continue.

What are some dos and don’ts and key success factors that the microfinance sector can learn from the Partner case? CFI’s forthcoming report, Weathering the Storm II, will draw on lessons from Partner and cases from microfinance institutions in four other markets: Azerbaijan, India, Palestine and Bosnia and Herzegovina. See also the original Weathering the Storm report from 2011.