Inclusive finance is driven by consumer data more than ever before. Whether it is a fintech leveraging alternative data for underwriting or platforms matching gig workers with opportunities, consumers are sharing unprecedented amounts of information about themselves with providers. At the same time, governments around the world have passed, or are gearing up to pass, comprehensive data protection laws such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that aspire to protect and empower consumers from data-related harms. A perspective that is sorely lacking amidst the fast-changing business models and emerging regulations is that of the consumer. There has been scant research that surfaces consumers perspectives on the use of their data and the data ecosystem, with most studies conducted in developed markets.

This brief shares highlights from a qualitative study in Rwanda of 30 mobile money users, conducted as part of our partnership with FMO to advance responsible digital finance. The survey focused on user perceptions of and opinions on consumer data in underwriting and the evolving data ecosystem. Given the growth of digital finance in Rwanda, supercharged during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the imminent passage of a data protection law, the following perspectives from Rwandan consumers are relevant for all stakeholders.

Our survey focused on user perceptions of and opinions on consumer data in underwriting and the evolving data ecosystem.

While mobile money was introduced in 2009 in Rwanda, the steady march to cashless experienced a rapid boost in 2020. In mid-March 2020, during the lockdown, the National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) acted to minimize economic fallout by temporarily zeroing out charges on transfers between bank accounts and mobile wallets, zeroing out all charges on mobile money transfers, and tripling the limit for individual mobile money transfers, among other measures. In addition to mobile money–based digital credit, fintech start–ups involved in lending have also sprung up in recent years, using alternative data sources to assess creditworthiness and extend financing solutions to the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector and the low-income population. The country is on the cusp of finalizing a Data Protection and Privacy Law. Emulating many aspects of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the law would give consumers new data rights such as the right to object, the right to information that a provider has about a subject, the right to correct or delete personal data, the right to explainability, and the right to data portability. With all of this activity, the question remains, how do customers feel about the use of their data?

Who is Fairer? Loan Officers vs. Digital Lenders

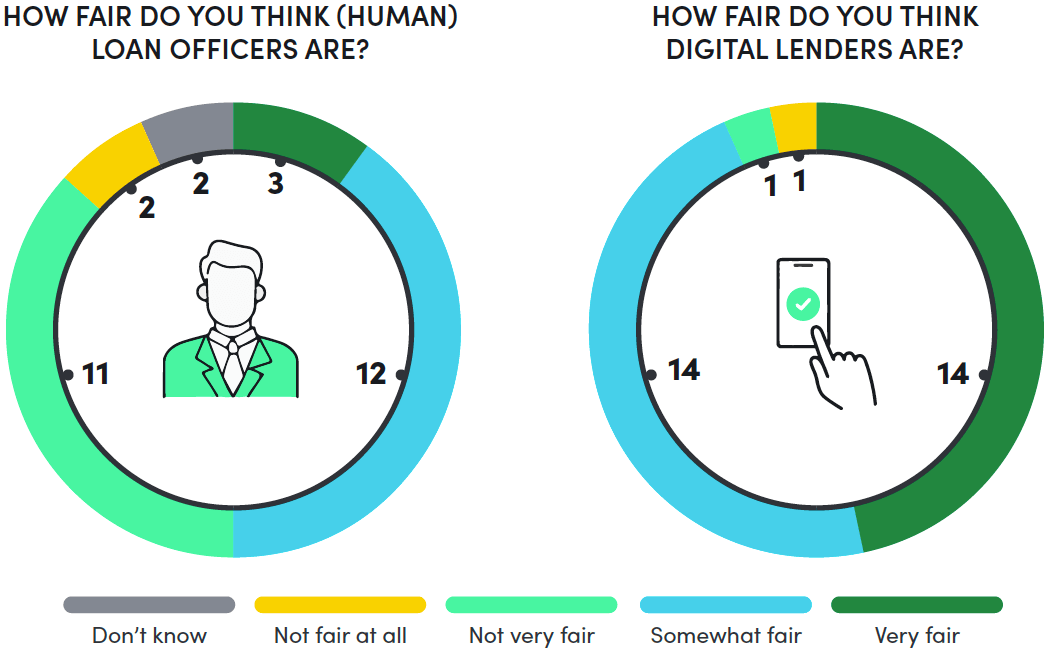

The decision of who receives and who is denied credit can be high stakes for individuals or businesses in need of a loan. Fairness in lending is embedded into financial non-discrimination law in many markets but does not guarantee non-discriminatory practices, nor is it clear in many jurisdictions how it is enforced against digital lenders. For analog models, loan officers — as the front-line client-facing staff of providers — are seen as the agents of fairness (or unfairness) in an underwriting decision. For digital lenders, an underwriting decision is made off-site, often within minutes, and by a computer. Participants were asked their perceptions of fairness of a loan officer compared to an automated system of a digital lender. Enumerators described fairness as making unbiased predictions about qualifications of a good borrower and not implicitly or explicitly discriminating against individuals or customer segments. Participants were asked to rank the fairness of loan officers and automated systems on a scale from “Very Fair” to “Not Fair at All” and share which of the two types of lenders they trusted more.

Of the 30 respondents, 12 described loan officers as “Somewhat Fair” and three responded with “Very Fair.” These respondents cited protocols and procedures at financial institutions that ensure creditworthiness assessments follow the stated rules, mentioning, “Loan officers follow well-established terms and conditions for the loan,” and “There are basic things that loan officers ask customers such as a collateral or employment contract.” For the 11 who said that loan officers are “Not Very Fair” and the two who said “Not Fair at All,” favoritism from personal relationships or family connections and corruption came up repeatedly, with respondents reporting, “It is rare to request a loan and the loan officer serves you well knowing that he will get nothing in return,” or “Human nature has a weakness of favoritism.”

When asked about the purely digital lenders, 14 responded that digital lenders were “Very Fair” and an additional 14 said “Somewhat Fair.” As to why they were “Very Fair,” respondents said, “Computers do not have feelings like human beings,” and “They give you a loan without hesitation as long as you fulfill the requirements.” Another respondent cited digital lenders’ imperviousness to bribery, saying, “People can be unfair if they know someone or if given a carrot (bribe), but automated computer programs cannot be induced.” For the two respondents who ranked digital lenders as “Not Very Fair” or “Not Fair at All,” their answers were linked to the lack of explanation when a loan is denied.

“People can be unfair if they know someone or if given a carrot (bribe), but automated computer programs cannot be induced.”

Given these results, it is not surprising that 80 percent of respondents confirmed that they would trust a digital lender’s credit assessment over a human loan officer. Our results indicate that most respondents believe that digital lenders overcome the human frailties that lead to unfairness and bias in traditional lending.

Fairness of Data Inputs for Digital Lending

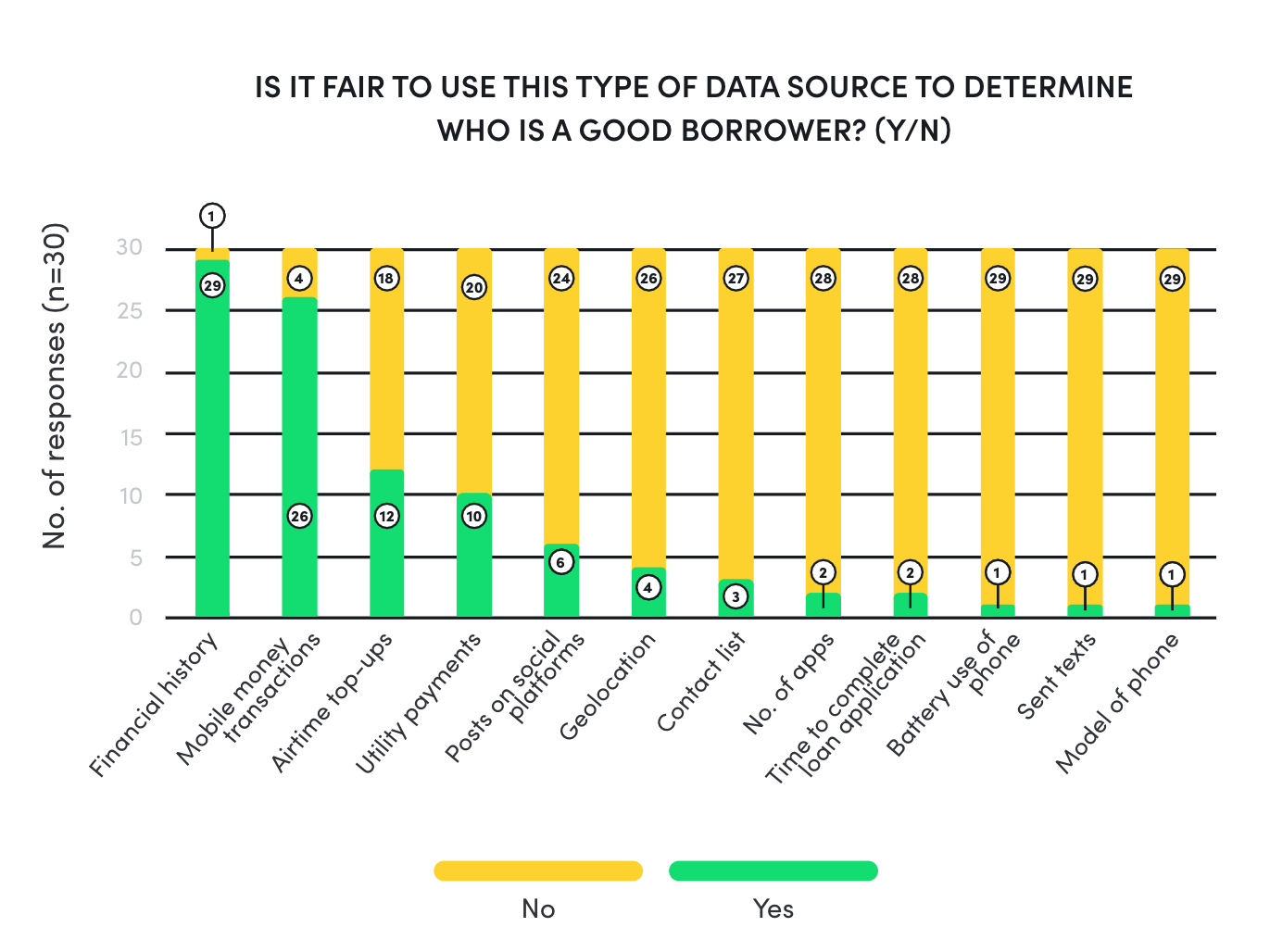

While our sample may profess to trusting digital lenders and their algorithms over loan officers, opinions become more complex when specific data inputs for credit decisions are highlighted. Respondents were asked the fairness of different data sources that digital lenders could use to assess creditworthiness.

Perceptions of Financial Data

Data types that hewed closely to financial behavior, such as financial history and mobile money transactions, were largely deemed fair by respondents. Respondents felt that these data sources conveyed financial status and financial discipline and needed transparency in the context of collateral-free digital lending.

Utility payments and airtime top-ups were not as favorably viewed, garnering only 10 and 12 positive responses out of 30, respectively. Respondents felt that utility bills were either too personal or private to share, that they should be siloed off from an individual’s repayment capacity, or that their absence due to an individual’s living situation (e.g., the prospective borrower is a tenant or lives in a rural village without utilities) should not negatively impact creditworthiness. Respondents were often very surprised that data like airtime top-ups, text messages sent, or utility payments could even be used to assess creditworthiness.

“They should not care about where I get money for my airtime. Being a good borrower is repaying your lenders well. Trying to know how much airtime you use daily is like trying to know how you eat daily.”

Respondents felt that using information about airtime top-ups was an invasion of privacy. A 29-year-old man mentioned: “They should not care about where I get money for my airtime. Being a good borrower is repaying your lenders well. Trying to know how much airtime you use daily is like trying to know how you eat daily.” Another said, “It is not the digital lender’s business to know whether the customer has loaded airtime or not.” Others felt that using airtime top-ups might exclude creditworthy groups of individuals: “There are casual workers who only receive calls. Therefore, topping up the airtime would be a waste. They rarely buy airtime and that’s for emergency cases.”

Perceptions of “Alternative” Data

When respondents were asked about the fairness of alternative data, such as number of texts sent, number of apps (on phone), model of phone, battery use of phone, posts on social media, and geolocation, support dropped precipitously. None of the alternative data categories garnered more than six positive responses out of 30. Respondents cited reasons ranging from the belief that this data was private and none of the lender’s business, to the risk that using this type of data would exclude certain groups, to the concern that this data type was unrelated to being a good borrower.

“Don’t you know that there are people out there who buy a certain phone to impress others, yet they have nothing in their pocket or on their account?”

A 45-year-old male respondent unpacked why using cell phone type is a suspect choice for use in underwriting: “If they considered the make and model of a phone, there are people who would sell their fixed asset to buy an expensive phone that would allow them to have access to a bigger loan. Don’t you know that there are people out there who buy a certain phone to impress others, yet they have nothing in their pocket or on their account?” The frequency of text messages sent had almost universal disapproval, with only one respondent saying it was a fair source for underwriting. A woman from Kigali said, “Many people no longer use text messages these days, yet they can pay back the loan.” Another commented that “the majority of text messages are sent and received by teenagers, especially those between 18 and 20. They have enough time to exchange text messages. Adults only send useful text messages.” Others were concerned about exclusion: “If I am a trader who can send or receive 20 messages in 10 minutes depending on what I am selling, this will not be the same for the person who works as a cleaner, yet we can all repay the loan.” Another female respondent commented, “There are people who did not go to school and therefore they can’t read and write. Some people would be left out.”

Taken together with the previous section, these findings suggest that while consumers might at first glance give a blanket approval of data-driven digital financial products, as the curtain is peeled back on how those products work, their opinions become more mixed.Social media’s role in underwriting was predominantly seen as private and unrelated, with 80 percent of respondents saying it was unfair. “The data on what you post on Twitter or Facebook … are my private data and they should not have any relationships with my digital [financial] account,” said a 32-year-old male respondent. “Your social media activities have nothing to do with the loan. We post when we are sad, happy, or when we want to share our thoughts with people. This has absolutely nothing to do with paying back the loan or not,” said a 32-year-old female respondent. However, six respondents did think that social media data was fair game, with one 29-year-old man conveying the sentiment of: “What you post defines you. You can post something that would tarnish your reputation and they would not give you a single coin. Posts can make [providers] trust you or not.”

Perceptions of Data Rights

Omnibus data rights legislation, like the GDPR and the draft Rwandan Data Privacy law, enumerates rights for consumers — including the right to rectification, the right to data portability, the right to object, and the right to an explanation/information behind an automated decision, like digital underwriting. But will Rwandan consumers, and others in emerging markets, have the awareness of how their data is being used to take advantage of these rights? The survey asked respondents about their experience when they were denied a digital loan, as well as the likelihood they would ask providers to rectify a data error.

While consumers might at first glance give a blanket approval of data-driven financial products, their opinions become more mixed as the curtain is peeled back on how those products work.

Right to an Explanation

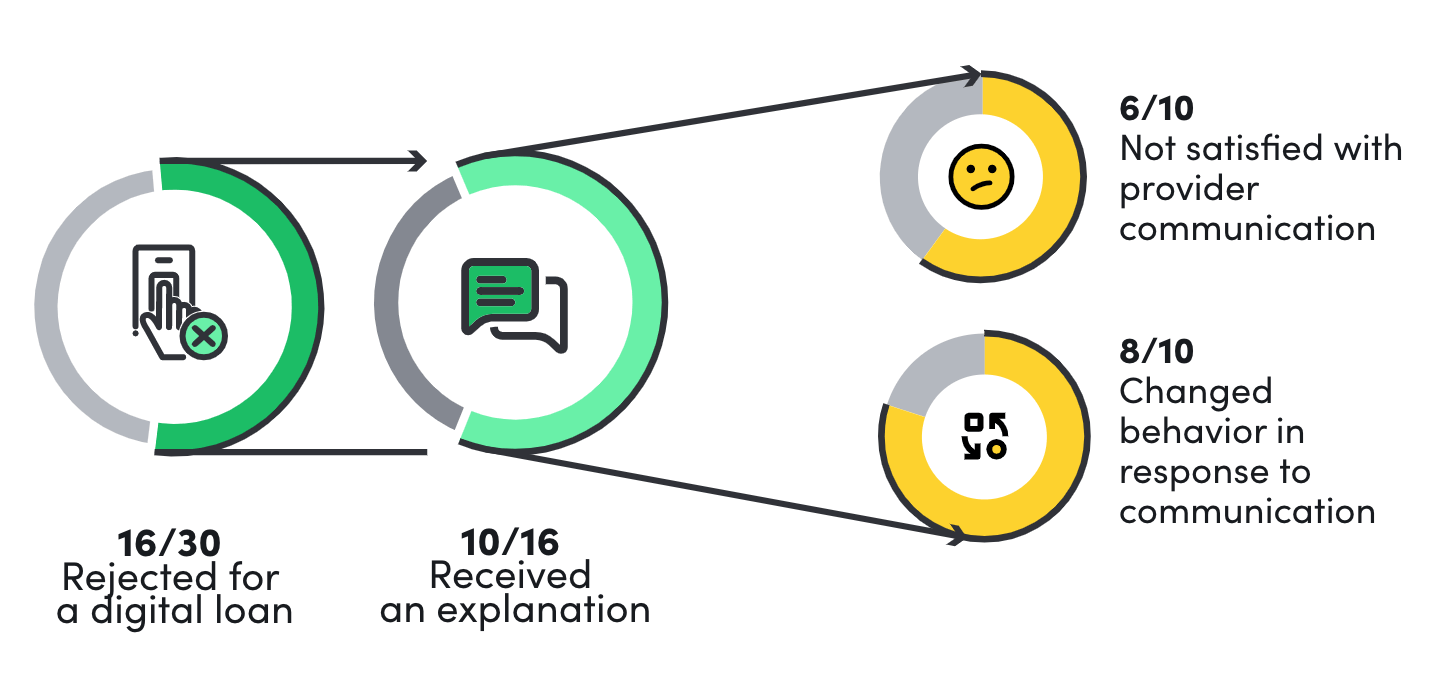

Through the GDPR and what has come to be known as the right to an explanation, individuals in many markets have the ability to obtain meaningful information about the logic involved in an automated decision made by an algorithm or other advanced analytics, such as the decision behind rejecting or approving a digital loan application. Article 39 of the draft Rwandan Data Privacy framework requires that providers inform individuals about the logic involved in their automated decision at the time of personal data collection; however, what this might look like in practice is unclear. To understand how explainability is currently perceived by consumers, respondents were asked about their experiences when denied a digital loan.

Sixteen participants out of the 30 had the experience of being rejected for a digital loan, and 10 of those recalled receiving an explanation for the denial. A few rejected applicants described a somewhat basic explanation such as, “Your credit limit is zero,” without further details, while others recounted more detailed instructions to “clear the balance on a previous unpaid loan,” before reapplying. “I only saw a message saying that I need to use Mokash for at least three months before applying for a loan,” said a 29-year-old female respondent. Six of the 10 participants who received an explanation were not satisfied with the provider’s communication. Despite mixed reviews of the provider’s explanation, eight out of the 10 respondents who recalled receiving explanations changed their behavior in response. Some began repaying their existing digital loans in a timelier fashion, while others increased savings and transactions within their mobile wallets.

“When you delay to repay, they call to remind you about the loan. They should then do the same when you are denied a loan.”

When the full sample was asked what an acceptable explanation of loan denial might look like, there was a universal request for more specificity and more communication. A 52-year-old woman shared her experience, saying: “They denied me a loan because I delayed to repay when I was in a hospital and very sick. If they had called to explain the reason for the denial, I would have explained my condition. Also, if they had told me that the delay would disqualify me from getting a loan in the future, I would have done everything in my power to repay on time even though I was hospitalized.” A 38-year-old woman reasoned: “When you delay to repay, they call to remind you about the loan. They should then do the same when you are denied a loan.”

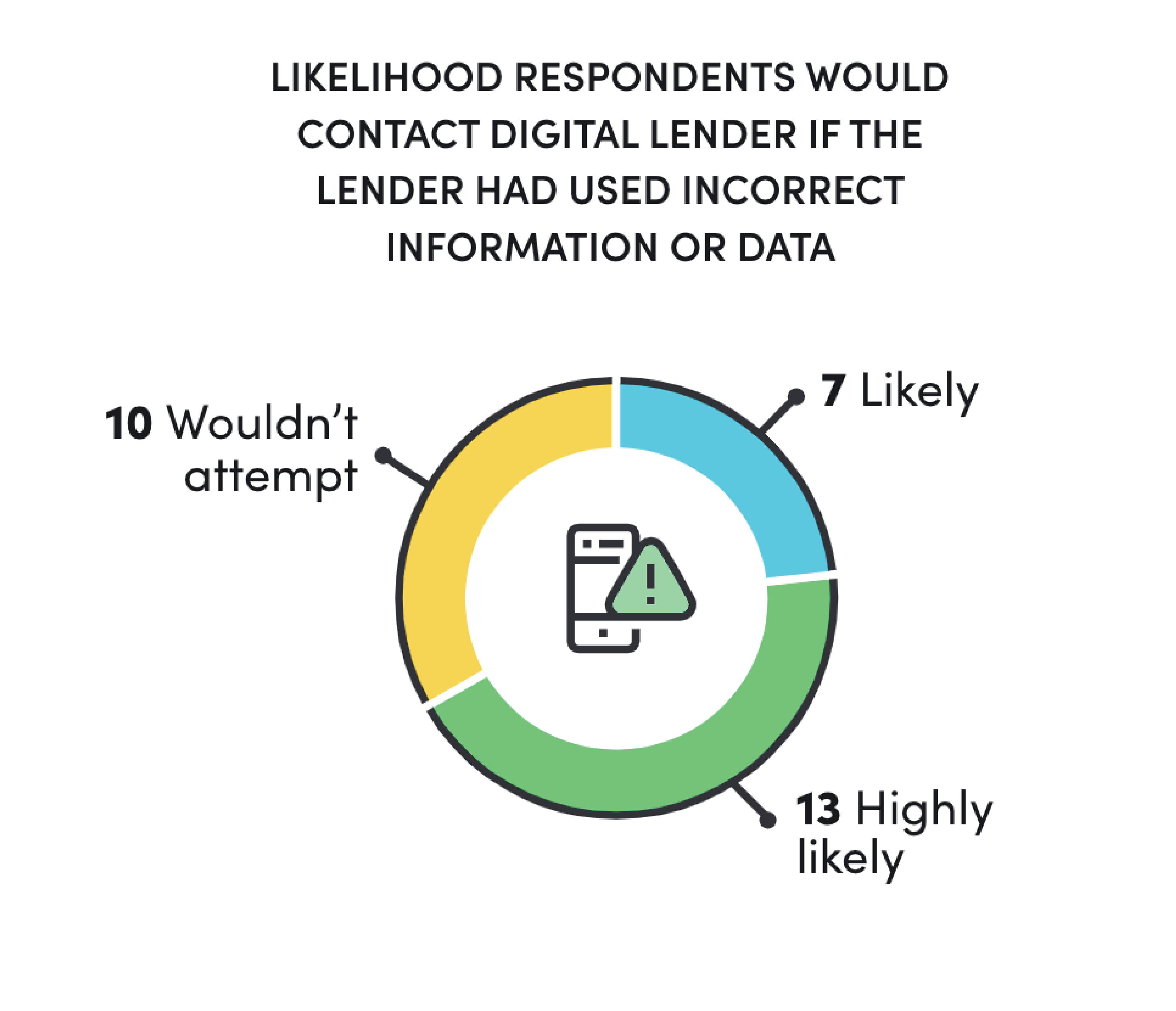

Right to Data Rectification

memorialized in the GDPR and the many frameworks that it has influenced, such as Article 25 of Rwanda’s draft data protection bill, consumers now have the right to ask data processors to correct inaccurate information. If this legislation passes, for digital credit, consumers could request that a lender rectify incorrect or inaccurate data about them that feeds into their risk profile. Respondents were asked how likely they were to contact a digital lender if they realized they were using incorrect information or data about them. Two-thirds of participants said they were either likely (seven respondents) or highly likely (13 respondents) to ask for their data to be rectified, while 10 participants said they wouldn’t attempt it. For those who wouldn’t pursue the rectification, the reason was not lack of empowerment but rather the tediousness of existing call centers, such as generic mobile money hotline numbers. “The hotline to call is always busy. In most cases you try up to 20 times without a response,” mentioned a 35-year-old male respondent. Many respondents mentioned they would go directly to a service center and bypass the call center entirely.

Conclusion

Given the growing importance of consumer data in inclusive finance and the potential for data-related harms, it is imperative for all stakeholders to understand the consumer perspective. This study — despite the small sample — illustrates that while consumers believe in the promise of digital finance, there are concerns around the data-related aspects of product design and the source of such data collection.

More research is needed to further understand consumer perceptions and opinions about the data ecosystem that increasingly determines their economic opportunities., and CFI is committed to exploring the topic further. Such insights from consumers would be crucial information for market actors to: 1) design better products and services; 2) design customer-centric data protection regulation and supervision; and 3) amplify the voices, concerns, and experiences of the most vulnerable. Methodologically, CFI’s work would also aim to advance how to design qualitative and quantitative survey instruments to best elicit useful information from consumers for such a frontier and complex topics.

About This Study

This research was a series of 32 qualitative semi-structured interviews to explore consumer perceptions, behavior, and knowledge about the data ecosystem driving digital financial services in Rwanda. The respondents were drawn from a subset of 1,200 participants in the 2018 Smart Campaign’s client voices survey. The interview guide was designed by the Center for Financial Inclusion (CFI) and carried out by Laterite, a development-focused research firm based in Kigali. Laterite drew the sample from a group that was among the digital vanguard, as measured by their applying for a digital loan in 2018, with the assumption that they would be in the best position to understand the data ecosystem. The sample size was initially 32, but after data collection, two respondents were dropped, and analysis was conducted on 30 — evenly split into 15 male and 15 female respondents, with an average age of 39. Laterite conducted qualitative interviews in the first quarter of 2021 which, given the COVID-19 pandemic, were conducted over the phone in Kinyarwanda to minimize contact between participants and researchers. Interviews were captured on a tablet using Survey CTO’s computer-assisted telephone interview (CATI) software; after translation and data cleaning, CFI analyzed responses which included ex-post thematic analysis for some of the open-ended questions.

Caution is required in interpreting the results of the study, as they were not intended to generate widely generalizable results. Rather, they reflect the opinions and attitudes of a small group of urban digital consumers. Additionally, the interview guide was an initial foray into understanding consumer perceptions and attitudes around these complex topics, and thus some of the respondents may have misinterpreted a question’s intent.