Ram Krishna is the owner of a local grocery shop in the outskirts of Hyderabad.

“Yes, I have digital options,” he told ACCESS ASSIST in February. “But my customers pay in cash mostly. It’s convenient. I have no fear of fraud. I prefer it that way. I have to pay to my suppliers and workers in cash.”

Little did Ram Krishna know that his preference for cash, arising out of convenience and ease of doing business, was about to change. When the World Health Organization released a statement on March 9 recommending people turn to cashless transactions in March, and the Reserve Bank of India followed suit, it was evident that contactless and digital payments would get a significant push. Since cash handling carries the risk of contamination of COVID-19 and requires social interaction, many customers have started demanding and using digital options.

Survey: Micro-Merchants are Weary and Skeptical

However, despite strong political will and government support to push the digital agenda across India – not to mention the immense potential of a cashless economy – micro-merchants have been weary and skeptical.

This is the conclusion of our dipstick survey of 50 micro-merchants in February across various sectors, from kirana shops (small convenience stores), small eateries, salons, vegetable and fruit sellers, to medical shops and mobile shop owners. We sought to understand and identify barriers to adoption of cashless modes of doing business. The study used in-depth interviews and focused discussions with micro-merchants from the cities/towns of Delhi, Krishnagiri (Tamil Nadu), and Guntur and Hyderabad in Telangana.

We sought to understand and identify barriers to adoption of cashless modes of doing business.

The interviewees had revenues ranging from $13,500 to $170,000, average margins of 15 to 20 percent and average transaction sizes ranging between $2.25 to $3. Seventy percent of the respondents were less than 50 years old. Ninety percent of respondents owned smartphones and 98 percent of them had either secondary or tertiary education. Almost all of them had at least one bank account and 84 percent made personal payments digitally. Seventy-five percent of the retailers who had not adopted digital payments had all the basic prerequisites for adoption (bank account, a smartphone, internet access and basic literacy).

Barriers: Infrastructure, Supporting Services and Demand

The barriers to adoption of digital payments were explored by analyzing the responses of the retailers who had either not adopted the digital payment instruments or had adopted, but with limited sustained usage rates. The survey also inquired about possible challenges they anticipated in adopting and using the digital payment instruments. The anticipation itself acted as a deterrent for micro-merchants to adopt digital payment instruments.

On the supply side, infrastructure-related issues like uninterrupted power supply and slow speed of internet remained a challenge. Inconsistent and unreliable technological infrastructure and poor capacity building support in rural and peri-urban markets to support electronic payments were found to be important reasons of non-adoption.

On the demand side, having access to POS machines and the convenience of cash were the top reasons for micro-merchant’s disinterest in adopting digital modes, with 23 percent of respondents echoing this as primary concern. One example is from the Krishnagiri semi-urban area, where a retailer applied for POS with his local private bank. In spite of regular follow up for more than 4 months, the bank was unable to provide a POS machine.

Twenty-three percent of the respondents mentioned weak aggregate customer demand. Their customers usually set aside monthly household expenses and prefer transacting with cash as it helps keep expenditures on budget. Even during the pandemic, the preferred mode of payment for this segment remains cash.

Customers set aside household expenses and prefer transacting with cash as it helps keep them on budget.

Sadly, 12 percent of respondents tried going digital, but subsequently discontinued due to insufficient demand, low perceived benefits and added complexity of operation. Complexity of handling POS machines, inability to handle unusual transactions — especially when they fail due to technical errors or poor internet — were key concern areas for many retailers.

No One to Show Them How

Moreover, shop owners do not have access to help from peers or family members to guide and facilitate the use of technologies for digital payments. In local neighborhoods, availability of the service providers for troubleshooting issues was also limited to mobile phone repair and internet connectivity fixes in most cases.

Among the respondents, 12 percent of the micro-merchants were unaware of the possibility of accepting digital payments, signaling a strong need for targeted communication strategies. Fifty percent of retailers who were not using digital payments mentioned they were not aware of the process of accessing digital modes. Neighborhood grocery retailers, which usually serve local households, refrain from using digital transactions, citing small size and scale of their businesses.

Moreover, they felt that installing digital payment instruments would be an unnecessary cost. Bigger department stores usually can streamline the operations and financial management to offset costs from fees, but 12 percent of respondents mentioned they operate on thin margins, and any cost escalation eats away at those margins.

Fear of Fraud and Lack of Trust

The fear of fraud stemming from a lack of trust of employees processing payments was also observed. All of the sample respondents mentioned payments being handled by owners or family members and in cash. The only exception was observed in a medical shop where the POS machine is integrated with inventory and billing. Such integrated application helps address the fear of manual error from retailer’s end; however, it comes with the tradeoff of becoming formalized and having to deal with tax requirements and compliance.

Leveraging a Critical Link: Suppliers

It will be equally critical to identify the key leverage points for improving digital payment adoption at scale. One leverage point is suppliers.

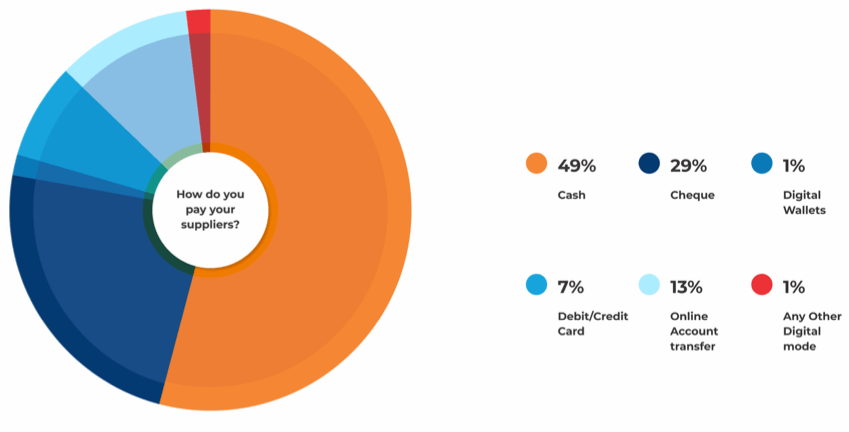

A broken link in the digital payment value chain is usually third or fourth stage distributors. Such suppliers or distributors demand cash from retailers, which in turn had a cascade effect. In fact, 49 percent of the sample respondents made cash payments to suppliers while 29 percent made check payments leading to a whopping 78 percent of respondents using non-digital modes for supplier payment.

Any digitization effort aimed at improving last-mile micro-merchant’s adoption rate should also push for adoption at the supplier’s end as well. Appropriate incentive structures for increased digital adoption need to be carefully thought out and incorporated into supply chains.

Leveraging Peer Support

The merchants’ peer networks played a prominent role in influencing merchants’ behavior and propensity to adoption of digital modes.

Retailers rely on tech-savvy friends for receiving or making payments through applications.

Peers accepting digital modes of payment helped to weaken inhibitions of others. Early movers in the peer group act as critical influencers: they discuss the benefits or challenges of digital adoption, which either weakens or reinforces inhibitions. Many retailers mentioned that they rely on friends for receiving or making payments through applications like GooglePay or online transfers. All the retailers mentioned that their friends were “tech-savvy” or “reliable” – and free.

The core value proposition of accepting digital payments – a secure, efficient and convenient way of being paid – needs to resonate with the merchants’ business needs. While we mobilize efforts and resources for increasing access and usage of digital financial services to bring back normalcy in post-COVID times, let us not ignore the key barriers and challenges last-mile retail units face.