Series

CFI is undertaking a global landscape of financial capability innovations.

Sound familiar?

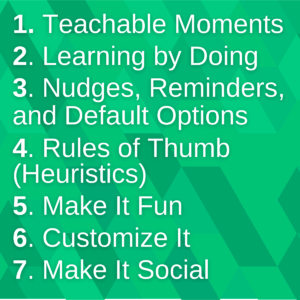

That’s because this research follows up on the landscape we published in 2016, which did the same. At that time, the financial capability landscape was fairly nascent – most traditional providers were still conducting financial education in classroom-like settings. The innovators – mostly fintechs – were taking a more behaviorally informed approach, tying financial education to everyday customer inflection points such as delivering key information at the point of a transaction or transfer, building a skillset by teaching the customer as they navigate a product or process, tailoring the approach to unique customer needs, and/or leveraging social platforms to encourage and promote financial goals and choices. We were optimistic that our seven principles of effective financial capability interventions provided guidance to providers that needed to move their knowledge and skill-building closer to the customer.

Since that publication, we’ve further fleshed out our thinking on the topic. In 2020, CFI published its MSME Financial Health Framework to evaluate and provide guidance on the drivers of the financial health of MSME entrepreneurs. CFI is also developing an app called FinVenture that utilizes best practices from financial capability and behavioral research to improve customers’ financial well-being. Now, we’re setting out to capture another global view because the financial landscape has only gotten more complex and crowded since 2016, brought on by two main trends:

- a proliferation of fintechs and digitally-enabled offerings, such as chatbots, mobile apps, and nudges and reminders as features of seemingly every product; and

- a growing awareness of the digital and financial gender divide.

All of this has become more important as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited physical mobility and in-person meetings, causing providers to pivot to digitally-enabled financial capability solutions.

Digital technology has allowed traditional providers to embed nudges and reminders into their delivery models, or provide information and services closer to the customer via agents, trusted intermediaries, or community members. Digital technology has also allowed all types of providers to bring targeted messages and products directly to the customer, but it also requires customers to have the skills to use and navigate digital technology. And while more and more people have access to mobile phones globally, we also know that billions do not and that the digital divide is even more pronounced for female customers.

While the rapidly changing and complex landscape is reason enough, this time we are taking a gender lens to our approach, asking specifically about building women’s financial capability. Low-income women are more likely to have low levels of financial literacy than men. In developing contexts, there are more out-of-school girls than boys, limiting opportunities for learning financial skills taught in school. Early marriage has detrimental knock-on effects on girls’ learning opportunities and earning potential. In addition to fewer formal learning opportunities, social and gender norms – informal and invisible rules governing people’s behavior – determine women’s care responsibilities and time use as well as limit women’s mobility, labor force participation, and the makeup of their networks (women and men tend to move in different social spheres, which may mean more limited political and economic influences). Low-income women in developing countries tend to work in the informal sector; in Africa, 90 percent of employed women are in the informal sector. Informal sector work often leaves workers vulnerable and with limited social protection policies, women are left with particular needs and knowledge gaps when it comes to building financial capability. Women are also less likely than men to have access to a phone, and far less likely to use mobile internet, for example, leaving them with fewer alternate learning channels.

The digital divide is even more pronounced for female customers.

With this context, we want to know which delivery models are optimal for which targeted female customer segments. And we set out to understand the importance of building digital capability as a complement to financial capability given the expansive use of digital delivery channels.

Building financial capability is a central component to financial inclusion. Indeed, informed and empowered men and women make less risky financial decisions than those with less knowledge. Financial products and systems remain fundamentally complex, particularly for people with low financial literacy. A household budget, saving for business investment, or managing an unforeseen emergency can cause chaos in the most adept household, let alone those experiencing the vulnerability and volatility of poverty. Building the necessary skills to navigate financial tools and normative obstacles can take time and creativity. While recent evidence shows that financial education can have meaningful impacts on individuals, evidence focused on disaggregated impacts – not just sex-disaggregated, but any type of segment disaggregation – of financial education remains scarce, frustrating progress on these key questions.

Taking a Community View

Building women’s financial capability, therefore, must take a community view – seeing women as part of a larger ecosystem that impacts their opportunities to learn, apply the information, and make economic decisions for themselves and their families. Financial education may be an individual study, but financial capability involves many more players.

Successfully building women’s financial capability must account for the systemic barriers women face. For example, a well-designed chatbot or IVR education series may provide flexibility, increasing women’s likelihood of taking in the information when she has time. A well-trained financial community champion familiar in a neighborhood may be able to navigate resistance to involving women in household decision-making, increasing her choices in her economic sphere. A workplace digital financial literacy program can reach women on their own terms, providing them with relevant information and skill-building when navigating digital payments for the first time. All of this has become more important in light of the pandemic, which increased the number of digitally-enabled financial capability solutions.

Successfully building women’s financial capability must account for the systemic barriers women face.

Our global landscape research of financial capability innovations takes these specific constraints into account. We’ve interviewed more than 30 financial service providers, financial inclusion and women’s economic empowerment programs, thought leaders and donors to find out which approaches are working well to serve different female customer segments and where there are gaps in our understanding.

Our research will likely be published in spring 2021, but we will be sharing our analysis in a blog series. Up next, we will explore a few examples of providers navigating women’s specific needs when building financial capability.