In recent years, people all over the world have increasingly wanted greater agency and control over what information about themselves is shared. This heightened awareness is unsurprising given the relentless tracking of consumers’ digital footprints, instances of data misuse by big techs and fintechs, and major security breaches such as India’s Aadhar data fiasco and the recent leak of health records of COVID-19 patients in Indonesia. Data errors, biases, and privacy breaches can have grave consequences for all consumers, and particularly for low-income consumers with limited digital and financial capabilities. Data and privacy breaches can result in an increased risk of fraud, job loss, shame, and rejected loan applications or overpriced loans and other financial services, including insurance, and above all, these breaches widen the economic divide.

Policymakers increasingly recognize people’s vulnerability to data abuse and the irreparable harm that can occur in a digital and data-driven economy. In response, many countries have recently passed new data protection legislation — including China, the UAE, Brazil, Russia, Switzerland, and Rwanda — to govern the collection, use, and dissemination of personal data. As new frameworks are introduced and operationalized, it is critical for inclusive finance stakeholders to understand the perspectives of low-income consumers and their attitudes and behaviors around the use of their data.

As new frameworks are introduced and operationalized, it is critical for inclusive finance stakeholders to understand the perspectives of low-income consumers and their attitudes and behaviors around the use of their data.

To provide light on this subject, the Center for Financial Inclusion (CFI) is conducting qualitative research to better understand consumer perspectives on the uses of personal data. In 2021, CFI released research on mobile money users in Rwanda, which found that while consumers believe in the promise of digital finance, there are concerns regarding the data-related aspects of product design and the source of data collection. Following the work in Rwanda, CFI conducted focus groups in Indonesia with 50 middle- and lower-middle-income urban smartphone and digital finance app users to dig deeper into the perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors around data privacy, sharing, and other potential risks in how digital finance apps use consumers’ personal data.

The digital economy in Southeast Asia is expected to reach USD$130 billion by 2025, with Indonesia anticipated to be the largest and fastest-growing in the region. With venture capital inflows of over $1 billion, the emergence of new unicorns Xendit and Ajaib, and the growing adoption of digital payments induced by the pandemic, the digital finance ecosystem in Indonesia is projected to soar to $8.6 billion by 2025. At the same time, the rapid ascension of thousands of peer-to-peer lenders, the majority of whom are not licensed by Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority, OJK, has given rise to growing concerns regarding fraud, personal data protection policies, and awareness of consumer rights. The country is on the verge of passing its first-ever Personal Data Protection (PDP) law that introduces a data protection officer and consolidates rules related to the ownership, transfer, and processing of personal data. The PDP law emulates Europe’s Global Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) — a legal framework approved by the European Parliament that provides stringent guidelines for the collection and processing of personal information from individuals living in the European Union. To date, 16 countries across North and South America, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East have implemented GDPR-like data privacy laws.

CFI’s research finds that although Indonesian consumers care about and value data privacy, their attitudes and behaviors when using digital finance often do not align. Challenges in understanding complex legalese, coupled with assumptions regarding the app’s safety and other psychological and contextual factors, make it difficult for consumers, especially low-income consumers, to incorporate adequate safeguards for data privacy. CFI’s research finds:

- Respondents value privacy but readily share data and apps with friends and family.

- Respondents think apps are safe and rarely read the terms and conditions, and never in their entirety.

- Respondents assume apps backed by the government can be trusted.

- Respondents are wary of fraud but consider data misuse to be less of a threat.

- Respondents are unwilling to pay extra for safeguarding their data.

The results of this research point to three key takeaways for policymakers, funders, and providers in Indonesia and other emerging markets: i) make privacy the default such that privacy is integrated into the design and essential to the functionality of the app; ii) incorporate data risks in digital financial capability programs; and iii) invest in more demand-side research to inform data protection regulation.

1. Respondents Value Privacy but Readily Share Data and Apps with Friends and Family

When the focus group facilitators inquired about what constitutes private information, respondents noted that household matters such as financial or marital problems, children’s academic performance, WhatsApp messages, and photo galleries on their phones are private and should remain confidential. One respondent stated, “Privacy is keeping my data and personal information secret and confidential. Others should not know about it.” Many mentioned that violation of privacy would cause shame and embarrassment, and some feared that it could also endanger their safety. Some also worried that disclosing their misfortunes could result in other people in their community being happy about their hardships.

However, respondents’ behavior seemed at odds with their stated desire for privacy. Most respondents were active on social media and freely shared posts about their successes, photos of their children, culinary accomplishments, and health status. While some set passwords that were difficult to guess, locked photo galleries, and even hid their salary and debt details from spouses, the majority were comfortable sharing phones, apps, and passwords with family and friends to play games or conduct ecommerce and financial transactions using their accounts. Women respondents described sharing their accounts on shopping apps such as Shopee, Lazada, and Tokopedia with siblings and friends, often placing orders on others’ behalf. A 41-year-old woman explained, “My sister sometimes uses my Shopee account for the verification code because her phone doesn’t support it. I am the only one with a Shopee account, so she borrows mine to make purchases.” Others mentioned that it was pragmatic to share apps given the space limitations on their phone, and most respondents had multiple social media profiles and accounts on ecommerce apps to take advantage of promotions using different email addresses.

Factors such as social norms, a perceived sense of control over one’s data, and a preference for tangible, short-term benefits over potentially harmful, longer-term impacts can limit consumers’ abilities to consider privacy in digital financial services.

Respondents also acknowledged that, while private, details of salary or debt amounts, Kartu Tanda Penduduk (Resident Identification Cards), Kartu Keluraga (Family Identity Cards), and land titles occasionally had to be shared to access credit. ATM PINs, while private, were occasionally shared with family and close friends to withdraw money during emergencies. Several women respondents explained that their PINs were created by family members. One woman said, “If I have to enter my PIN, I give it to my children because they are the ones who created it.” Another shared, “My husband created my PIN, so it is already being shared.”

While, at first glance, these findings suggest that consumers may not care about privacy, studies show that several factors dictate the desire to share information with one’s networks. Factors such as social norms (the implicit and informal rules, attitudes, and behaviors that encourage consumers to follow socially accepted practices), a perceived sense of control over one’s data, and a preference for tangible, short-term benefits over potentially harmful, longer-term impacts can limit consumers’ abilities to consider privacy in digital financial services.

2. Respondents Think Most Apps Are Safe and Rarely Read Terms and Conditions, and Never in Their Entirety

As part of the focus group discussions, facilitators read excerpts from WhatsApp’s terms and conditions to gauge respondents’ familiarity with the language and the concept of terms and conditions in general. While most participants in the focus group discussions acknowledged seeing the clauses when installing the app, no one had fully read them. Respondents explained that the text of the terms and conditions was too long, overly complex, and difficult to understand. Older respondents struggled with the font size. The majority reported that they usually skipped the terms and conditions while downloading an app and scrolled directly to the “I agree” section. Some also said they skimmed through the text and read what was “necessary” and highlighted in bold font. If confused by the language, some respondents said they turned to their children for guidance, who advised them to skip the text and not share account details with others as a precautionary measure. Women respondents sometimes turned to their husbands for permission or children for guidance when downloading finance apps.

More fundamentally, there was a wide variance in respondents’ understanding of what the terms and conditions represented. Focus group respondents provided myriad interpretations regarding what they thought was the purpose of the terms and conditions in digital finance and other apps. Some respondents believed that the terms and conditions clarified an app’s functionality. Others were of the opinion that the terms explained how apps prevented data theft by tracking criminals and blocking miscreants. A few respondents also thought the terms existed to reassure and convince users that the apps were safe.

Notably, several respondents assumed that the terms and conditions were the same across all apps, and therefore, there was no need to read them every time they downloaded a new app. Some also pointed to the power and information asymmetries between app providers and consumers, and how their options were limited if they had concerns about the terms. One respondent stated, “We can read it in detail, but we have to go back [and cancel the download] if we don’t agree with the terms.”

3. Respondents Assume Apps Backed by the Government Can Be Trusted

Because of the complexities of the terms and conditions, respondents often turned to others for cues, and the more widely used an app is, the more it is considered trustworthy and safe. As one respondent stated, “If everyone is doing it, it must be safe.” Respondents assumed that apps like WhatsApp were legitimate because Indonesia’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, Kominfo, had authorized its use. They also cited the clampdown on some illegal apps as examples of the government’s efforts to protect users. Similarly, respondents considered digital finance apps such as Kredivo and Home Credit to be trustworthy because they were licensed by OJK, Indonesia’s Financial Services Authority. One respondent expressed, “If a lending app [from a bank] is registered with OJK, we have protection. Otherwise, it is not safe and can’t be trusted.”

People often exhibit an illusory sense of control over their data, struggling to understand the true implications of how their information is used in the complex data ecosystem.

CFI’s findings resonate with Acquisti et al.’s research that people have limited attention spans and often exhibit an illusory sense of control over their data, struggling to understand the true implications of how their information is used in the complex data ecosystem. Consequently, they tend to trust the actions of their peer group. This dilemma holds in both developed and developing countries. Hartzog and others have estimated that the typical internet user would need 76 working days to read all the privacy policies they encounter in the course of one year. This “bandwidth problem” is exacerbated for low-income consumers and women, in particular, who have a limited understanding of the complex digital ecosystem.

4. Respondents Are Wary of Fraud but Consider Data Misuse To Be Less of a Threat

While nearly all focus group participants were sensitive to tangible risks such as fraud, cybercrimes, and the usurious lending practices of online lenders, respondents were less concerned about data misuse or informational errors. Respondents shared instances of acquaintances fraudulently using their information to obtain loans, ecommerce accounts being hacked, or suspicious phone calls asking for their PIN. Given these apprehensions, respondents were careful about downloading apps that were rumored to be unsafe. One respondent explained, “There was viral news about a Zoom data leak, so I was afraid to download it. I avoided using Zoom until recently. But, ultimately, I was forced to register because I needed the app.”

Respondents had not considered the possibility of app developers gaining access to their personal data to be a potential threat. In general, respondents believed that the apps were tracking their data to prevent its misuse, to understand customer behavior, and to provide tailored product recommendations. Respondents hoped their data would not be sold to third parties, and the consensus was that “even if apps sell our data, they may have their reasons, but it’s nothing to worry about.” This presumption was particularly true for global apps, such as WhatsApp, as respondents believed they could report issues directly to WhatsApp or escalate it to the country’s Ministry of Communications and Information Technology for proper resolution.

After probing, respondents conceded that it was likely that apps could access their photo gallery, messages, emails, contact lists, call data records, phone usage patterns, as well as IDs and any documents lending apps had collected. Until the focus group facilitators raised the concern, however, most respondents had never considered the possibility that in consenting to a service, they could be signing away their data rights and providing firms with blanket permission to use and sell their information. During the discussions, some respondents wondered if they were putting themselves at greater risk by using their social media accounts to log in to other apps. A few respondents assumed that in the worst case, they could simply delete the apps to keep their data safe.

5. Respondents Are Unwilling to Pay Extra for Safeguarding Their Data

To better understand how consumers value privacy, we asked respondents if they would pay more for a digital finance app that does not share their data. Given that most focus group respondents did not consider the risks arising from the sale and misuse of personal data, they were unwilling to pay extra for safeguarding their data. Respondents would only consider paying for an app if there was no free alternative available.

Respondents stated they should not have to pay for apps since the provider was benefiting from consumers using the app. Furthermore, they believed that they were indirectly paying for the app by being forced to view ads. Participants also voiced doubts about whether their data would be more secure if they paid for it. As stated by one of the men interviewed, “We have to be smart. We can’t easily trust anybody if it relates to our privacy.”

When given a tradeoff between price and privacy, customers almost always resort to the cheapest, less-private option.

These findings contrast insights from experiments conducted by CGAP in Kenya and India, which suggest that low-income consumers may be willing to pay more and spend more time obtaining a loan that offers greater privacy and protection. While more research is needed to understand these differences, it is important to recognize that, unlike the context of the CGAP research, CFI did not conduct a controlled experiment whereby participants are offered multiple options with different prices and privacy levels. Instead, through focus group discussions, we asked people about the notion of privacy and to what extent they would go to protect their data. CFI’s research findings align with several other studies that show that when given a tradeoff between price and privacy, customers almost always resort to the cheapest, less-private option, or they opt to part with their data in exchange for free pizza slices or other small, tangible rewards. Furthermore, for many respondents, the immediate convenience offered by social media logins triumphed over the longer-term, intangible risk of data misuse by app providers and third parties.

Looking Ahead

While policymakers and technology providers advocate for increased transparency, hoping that people will have sufficient understanding to self-regulate their data and provide informed consent, growing evidence suggests that privacy perceptions are highly subjective and, therefore, can be easily influenced by app providers. At the same time, people face numerous barriers in navigating the many apps that access their data and must constantly manage what information can be disclosed and what should be withheld to protect their privacy. Findings from CFI’s focus groups with middle- and lower-middle-income urban digital users in Indonesia show that despite being digitally active, people are ill-equipped to self-govern in a fast-moving data ecosystem. This issue is likely to be far worse for lower-income populations.

Our research highlights three areas that policymakers, funders, and providers in Indonesia and other emerging markets should consider as they work to create a safe and robust data ecosystem for inclusive finance consumers:

1. Make privacy the default.

As Indonesian policymakers and other stakeholders are strengthening the pending PDP law, CFI encourages the government to consider these findings and make privacy the default, integrating privacy measures directly into the design of the app. Low-income consumers often lack the baseline knowledge and capability to interpret complex legalese or understand how their mouse clicks and web activities are tracked. Consequently, policymakers need to incentivize providers to develop solutions where consumers are not required to self-regulate their data. Instead, privacy should be a forethought, embedded throughout the design and engineering processes, as laid out in Article 25 of the Global Data Privacy Regulations.

2. Include data risks in digital financial capability initiatives.

At CFI, we define digital financial capability as the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, and evaluate financial services offered through digital technologies. As the line between inclusive and digital finance is increasingly blurred, it is evident that digital and financial capability-building initiatives must go beyond financial and digital literacy and include components that help consumers understand and respond to data risks.

One of the most obvious reasons why, despite best intentions, consumers fail to consider privacy is a general lack of awareness about what data is collected and how it is disseminated and used. In this complex data ecosystem, the odds are stacked against low-income users with limited digital capabilities. For people to better protect their privacy and data, information needs to be available and presented in a way that is easily comprehended so consumers can be informed when using digital finance and other apps.

3. Invest in demand-side research across different contexts.

Data privacy is a complex issue. Unfortunately, research on understanding consumer perspectives — a crucial step to addressing these issues — is scant. CFI’s research contributes to insights on how people’s attitudes, perceptions, and social norms are evolving in this rapidly changing environment. Much more research — combining psychology, economics, computer science, and law — is needed to better understand how consumers engage with the data ecosystem and the costs, benefits, and potential long-term ramifications of different policy interventions that help consumers consider privacy.

About This Study

The author would like to thank the lead researcher Alex Rizzi, as well as Julia Arnold for supporting the research and Aeriel Emig for her editorial oversight.

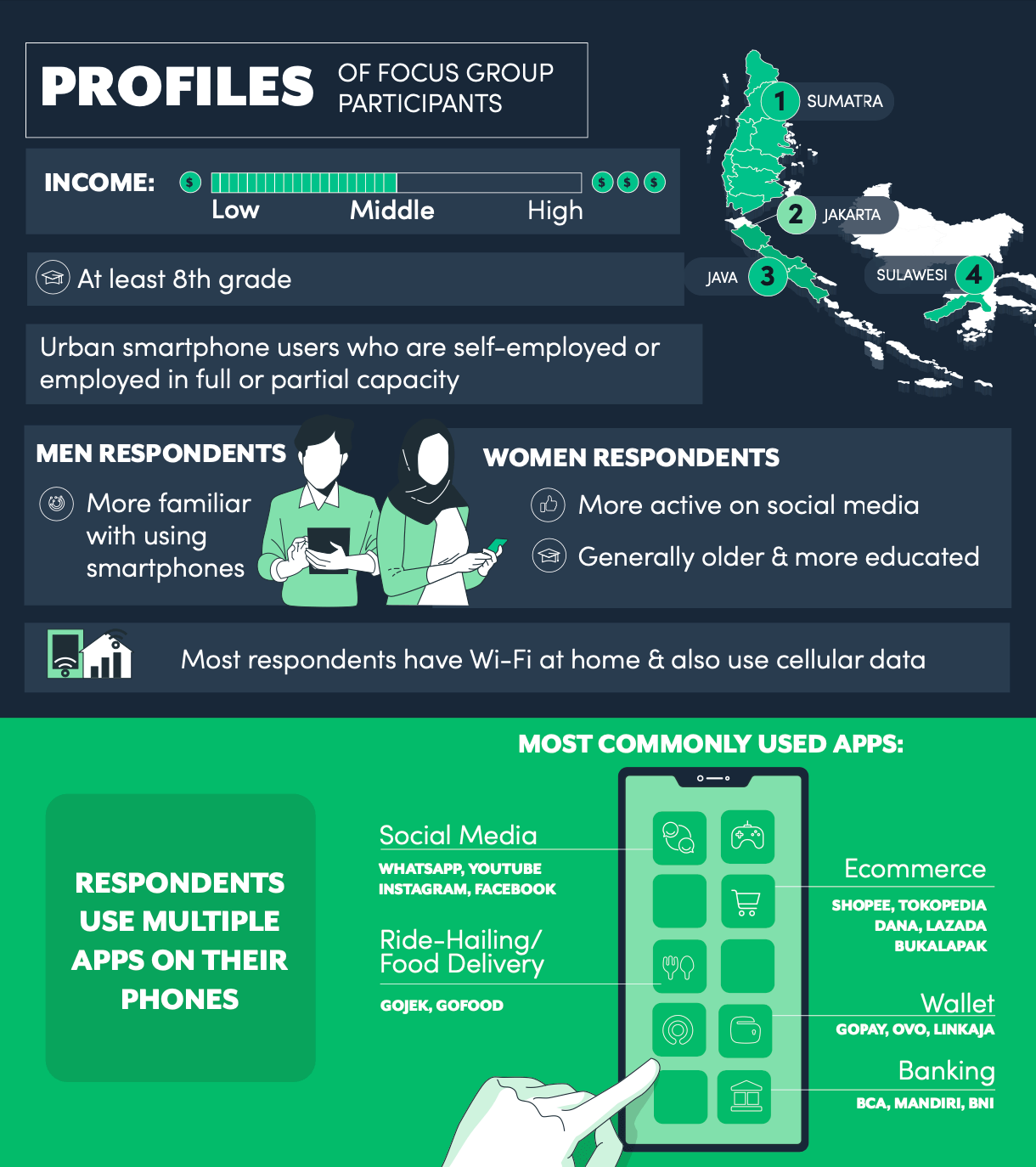

Through this research, CFI aims to test different research methodologies to determine what approaches can help elicit information from consumers on frontier topics. Previous research in Rwanda indicates that more open-ended and interactive approaches such as focus groups were best suited for nuanced discussions on complex, new concepts. To that end, this study involved a series of focus group discussions with 50 male and female urban smartphone users. Respondents were selected from Indonesia’s Financial Inclusion Insights Survey (FII) by the National Council for Financial Inclusion (Dewan Nasional Keuangan Inklusif – DNKI). The interview guide was designed by the Center for Financial Inclusion (CFI) and administered by Kantar, a global data research, insights, and consulting company. There were ten focus group discussions divided into six female and four male groups. Each group had five to eight participants from Jakarta, Java, Sulawesi, and Sumatra.

The goal of this research was to explore the opinions and attitudes of a small group of urban digital consumers and as such, caution should be used in interpreting the results as the study was not designed to be widely generalized.