This blog post was written by Swati Mehta, independent consultant and development researcher, and Liz McGuinness, Senior Director and thematic lead for Women’s Financial Inclusion at CFI, in collaboration with Astrid de Valon who leads the World Food Programme’s (WFP) work on Digital Financial Inclusion and Women’s Economic Empowerment. This is part of a series of CFI work done in partnership with WFP, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, that explores how we can improve the design and delivery of digital cash transfers for low-income women.

WFP’s New Policy Prioritizes Women to Receive Cash Transfers on Behalf of Their Households

Today, digital innovations are reshaping the way we manage money and helping to advance digital financial inclusion. Specifically, the digitization of cash transfers is helping to scale up humanitarian assistance and government-to-people (G2P) payments. However, unless these digital advances have a deliberate gender-focused approach, they risk missing the opportunity to advance women’s financial inclusion and increase their empowerment.

Recognizing the transformative power that directing cash transfers to women can have, WFP’s revamped cash policy prioritizes sending money to women’s accounts on behalf of their households whenever possible. WFP is the world’s largest provider of humanitarian cash. WFP provides assistance to the people who are most at risk of going hungry. Two-thirds of these people live in conflict settings, the majority are women, and many live in hard-to-reach areas with limited access to services. In 2022, WFP sent $3.3 billion to assist 56 million people in 72 countries, with cash-based transfers constituting 35 percent of all WFP assistance. Currently, 1.3 million women receive money from WFP on their own accounts for their families. With their new policy in place, WFP’s goal is to reach 10 million women in the next few years.

This policy change was supported by a series of studies run jointly by CFI and WFP to explore how providing women with their first access to digital solutions and financial accounts can lead to increased economic participation and reduce poverty in their households and communities.

CFI and WFP found that carefully designed cash transfer programs that send money directly to women on behalf of their households can not only enhance household well-being and increase women’s empowerment, but can often reduce the risks of intimate partner violence (IPV) as well.

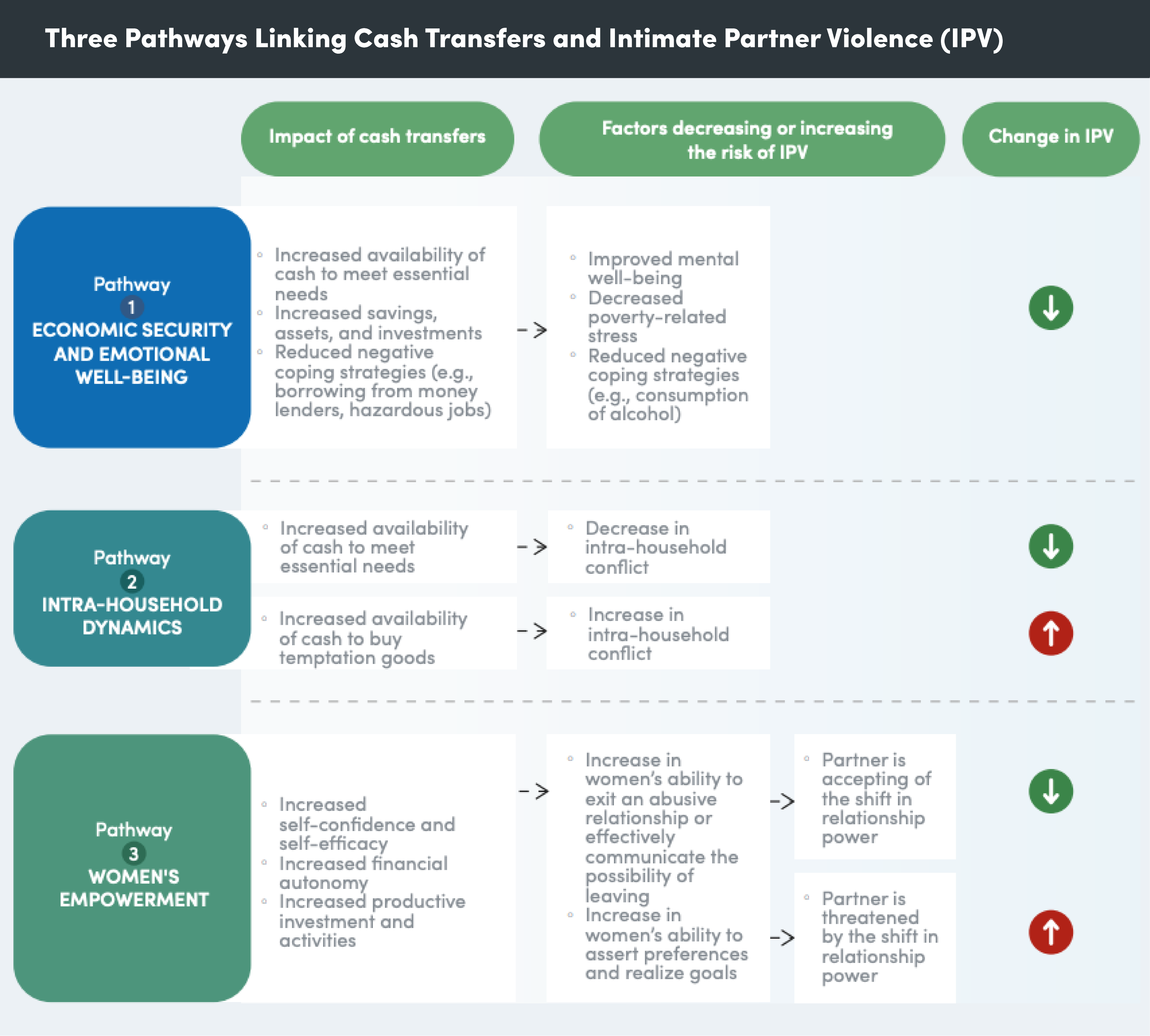

Sending money to women on behalf of their families raises several questions about potential risks that could come from changing how cash transfers are delivered and to whom. Through a comprehensive desk study and interviews with expert stakeholders, CFI and WFP found that carefully designed cash transfer programs that send money directly to women on behalf of their households can not only enhance household well-being and increase women’s empowerment but can often reduce the risks of intimate partner violence (IPV) as well. However, under certain conditions, cash transfers to women may still trigger instances of IPV in contexts where rigid gender norms are deeply ingrained. To understand these conditions, it is useful to examine the impact pathways and risk factors that link cash transfers and IPV.

Understanding the Link: Cash Transfers and Intimate Partner Violence

There are three pathways through which cash transfers can either reduce or exacerbate the risk factors associated with IPV. In one pathway, cash increases household income, thereby reducing conflict due to economic insecurity and related emotional stress. In these cases, cash transfer programs have proven to positively impact household economic security, leading to reduced reliance on negative financial coping mechanisms, enhanced emotional well-being, and reduced IPV.

Comprehensive studies across diverse contexts have consistently shown a reduction in IPV. A review of 22 studies spanning Latin America, Africa, and Asia found that in 16 of those studies, cash transfers resulted in reduced IPV. Another meta-analysis on the effect of cash transfers found that the bulk of the evidence pointed towards either a reduction in IPV or no change in IPV. There is an expanding evidence base arising from research conducted across diverse geographies and settings examining the role of complex design features and post-program impacts.

Other studies have shown that when transfers increase the amount of cash in the household, it may in fact increase intra-household conflict and IPV when there are disagreements about how to use the money, as seen in the second pathway. Similarly, programs in which cash transfers increase women’s economic empowerment through increasing their confidence or financial autonomy may shift household dynamics which can lead to either reduced or increased risk of IPV depending on whether there is a positive or negative reaction to women’s newfound status, as seen in pathway three.

The study confirmed that while directing funds to women’s accounts for their households can indeed bring additional benefits for women, they must be coupled with complementary initiatives to mitigate potential backlash resulting from the shifts in household dynamics.

How to Best Design Cash Transfers Prioritizing Women as Recipients on Behalf of Their Households

It is evident that there can be real benefits in directing cash transfer payments to women. Yet research is limited on the differential impact of IPV based on the gender of the primary recipient. Therefore, it is important to design interventions to mitigate any unintended IPV risks when cash is directed to women on behalf of their households. Experience and evidence suggest that policymakers and program managers pay special attention to how programs are executed and the context in which they are rolled out.

Execution Matters: Ensuring Sustainable Change

If programs are executed well, the reductions in IPV due to cash transfers could be sustained beyond the program term.

If programs are executed well, the reductions in IPV due to cash transfers could be sustained beyond the program term. While the evidence is still emerging, early studies and operational guidelines (see World Bank’s Safety First Toolkit and WHO’s RESPECT framework) have highlighted the important role of complementary interventions to sustain reductions in IPV risk factors. These include livelihood trainings or productive asset transfers to improve income; trainings and initiatives to improve household financial management; parenting programs or discussion groups to improve relationships between the household members; and programs to improve women’s confidence, economic standing, and social capital, such as through livelihood trainings, financial planning, and other group-based activities.

A promising example of this type of long-term thinking and practical training is WFP’s cash transfer program in Jordan. There, as WFP transitions from value vouchers to mobile wallets, women in male-headed households are specifically encouraged to open the primary wallet for receiving cash assistance. To ease this shift and promote household acceptance, WFP conducts information sessions for the heads of households and spouses to educate them on wallet setup, benefits, and usage. The training materials stress the importance of multiple wallets within the household, presenting it as a family-sharing solution. While changing entrenched gender norms takes time, this intervention saw 11 percent of male-headed households outside camps and 5 percent within camps registering women to receive cash transfers via her own mobile.

Context Matters: Impact on IPV in Diverse Settings

Our research emphasizes the importance of contextual factors in designing effective cash transfer programs that address IPV risks. In conservative contexts characterized by rigid gender norms, there may be a higher risk of backlash when women gain control over resources. This risk worsens in countries experiencing civil war or in conflict zones and among specific sub-groups of women, such as those with low educational levels or in households with constrained budgets or larger families. However, these settings also present opportunities for change by designing targeted interventions that empower women and thereby reduce exposure to some of the factors that make women vulnerable to violence. These include low bargaining power within household decision-making and a lack of control over financial resources.

Conservative settings present opportunities for change by designing targeted interventions that empower women, and thereby reduce exposure to some of the factors that make women vulnerable to violence.

In Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, WFP and its collaborating partners successfully engaged the community by identifying and training both men and women community champions. These champions were carefully chosen from households where women were designated as the primary recipients of cash transfers delivered through digital financial services. Their role was to support and educate the wider community on the numerous advantages of digital financial services, and to address any questions or concerns raised by community members. The men champions also sensitized other men in their community regarding women’s access to and use of financial services and how that benefits the entire household.

Looking Ahead

CFI and WFP’s research shows that well-designed cash transfer programs have the potential to enhance household well-being, contribute to women’s economic power, and reduce risks of IPV. But doing so successfully requires a nuanced approach that incorporates gender-transformative elements and engages multiple stakeholders. When done well, these programs can create an environment where women’s journeys are both secure and empowering. Economic empowerment for women is not just about dollars and cents; it’s about giving them the tools they need to thrive, the power to control their financial destinies, and the freedom to live without fear of violence. When cash transfer programs are designed intentionally, considering local context, they can help us move closer towards the goal of women’s economic empowerment, paving the way for brighter futures, stronger families, and more resilient societies.