When World Bank President David Malpass opened the Global Findex Launch event on June 29, he mentioned that giving people bank accounts – the key metric used to measure financial inclusion – “is not the lowest cost way of providing financial services,” and that the focus of financial inclusion should instead be on promoting higher transaction volumes and affordability of financial services. Malpass said, “In an ideal world […], you want to have billions of transactions but have the cost be a tiny fraction of a cent.”

Malpass’ remarks point to the long-standing effort among the inclusive finance community to revise its target metrics beyond access. On one hand, as Malpass pointed out, accounts are expensive and many low-income consumers prefer to transact through digital payments services without opening formal bank accounts. Moreover, among those who do have bank accounts, dormancy levels are high. Accion’s CEO Michael Schlein pointed out that in addition to the 1.4 billion people excluded from the financial system, there are also 400 million people worldwide who are underserved, meaning they have opened accounts but never use them.

1.4 billion people are excluded from the financial system, but there are also 400 million people worldwide who are underserved.

Every Global Findex release – this is the fourth in 11 years – is a moment of reckoning for the inclusive finance community. The 2021 results show where progress has been made in areas that seemed unachievable just a few years back – from Africa’s leapfrog into digital financial services to the narrowing gender gap. The World Bank Findex team also introduced new and enhanced indicators on financial resilience and financial “worrying” that, despite their limitations, are important additions and signal interest in richer and more meaningful metrics to evaluate consumer outcomes. Below are four findings that excite us and two suggestions on what we’d like to see in the next Findex.

1. Account Ownership Has Expanded to Record Levels in Africa, While the Arab World and South Asia Have Stagnated

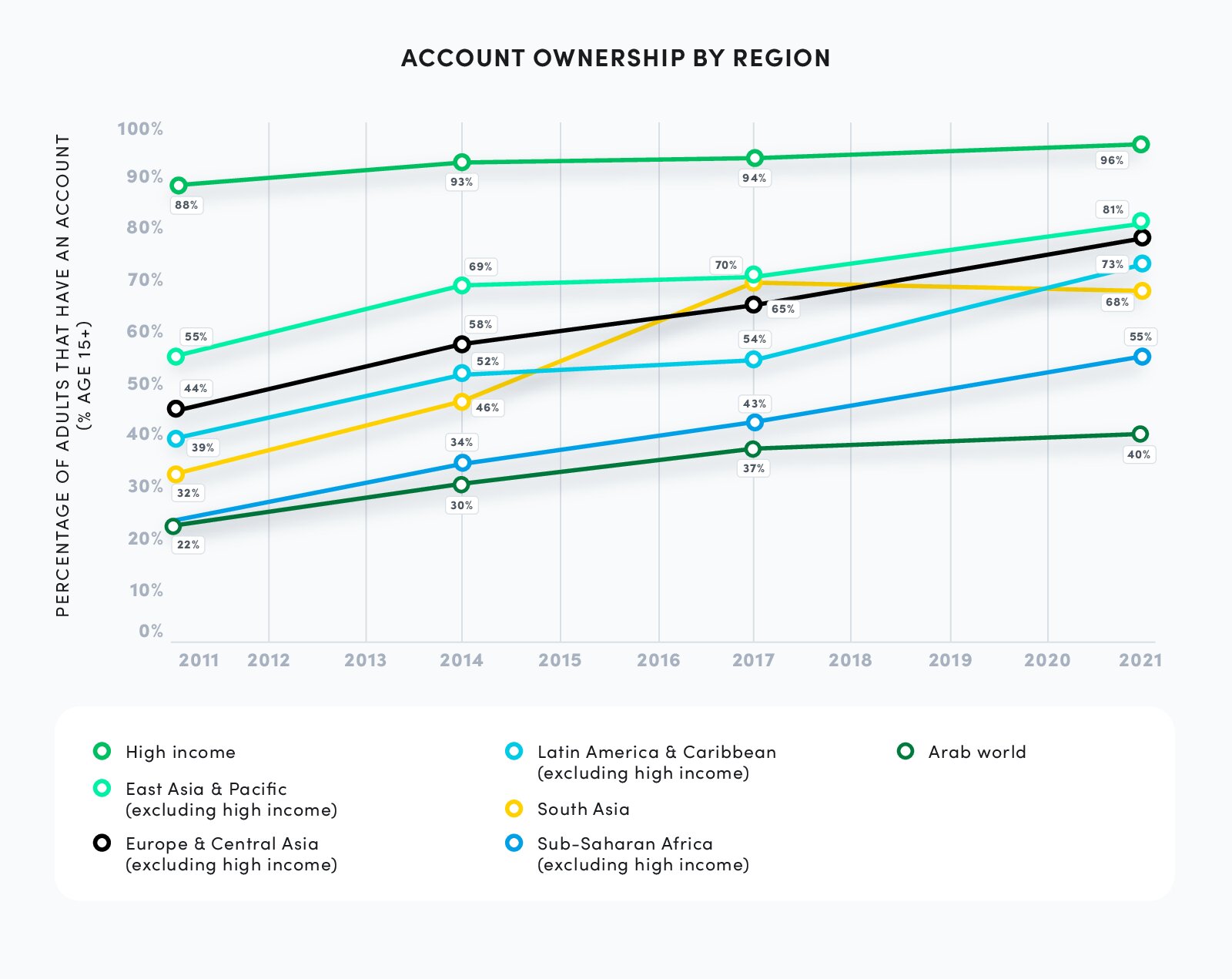

Between 2011 and 2021, global account ownership grew by 50 percent from 51 to 76 percent. This indicator grew at a higher growth rate (71 percent) in developing economies, increasing from 42 to 71 percent, which shows that many previously unbanked populations have since gained access to the financial system.

The region that saw the greatest growth in account ownership since 2011 is Sub-Saharan Africa, primarily because of the record uptake of mobile money services. Account ownership increased at a rate of 140 percent across Sub-Saharan Africa (from 23 to 55 percent), with Senegal, Gabon, and Uganda among the top 5 countries with the largest increase in account ownership. Conversely, the Arab World continues to experience slow growth in account ownership – with only 40 percent account ownership in 2021. South Asia experienced stagnation in account ownership – dropping from 70 percent in 2017 to 68 percent in 2021, a drastic change from the rapid increase in account ownership driven by the Jan Dhan Yojana program in India between 2014 and 2017. The change in both South Asia and the Arab World is within Findex’s margin of error of 3.5 percent.

2. Account Dormancy Continues to Be Significant in South Asia

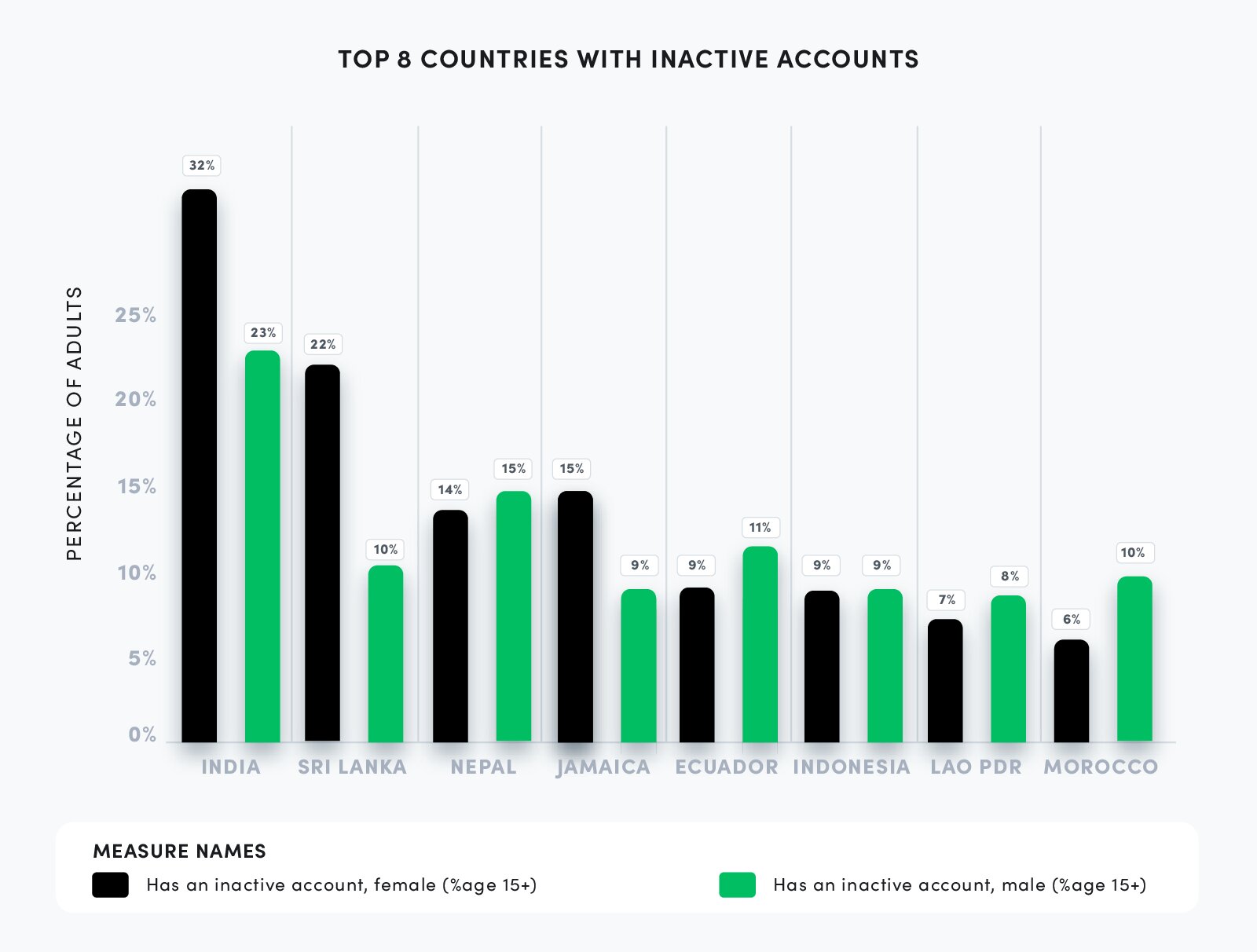

After the 2017 Findex release, CFI pointed out that a very large share of accounts were unutilized. Although the definition of inactive accounts has changed in the 2021 Findex to now include “not making any payments” in addition to “not making deposits and withdrawals”, the figure remains high: more than 400 million people globally have an open account but have not used it for over 12 months.

India has the highest rate of account inactivity. Despite the progress enabled by Aadhaar and the Unified Payment Interface – India’s digital identity and payment infrastructures – the levels of account inactivity are the highest in the world and are particularly high among women: almost one in three Indian women (32 percent) have dormant accounts, 9 percentage points higher than for men. Sri Lanka and Nepal have the second and third highest levels of account inactivity (16 and 14 percent, respectively). When we exclude India and Sri Lanka from the calculations, men and women in developing countries have similar levels of account inactivity.

3. Redrawing the Global Map of Financially Unserved and Underserved

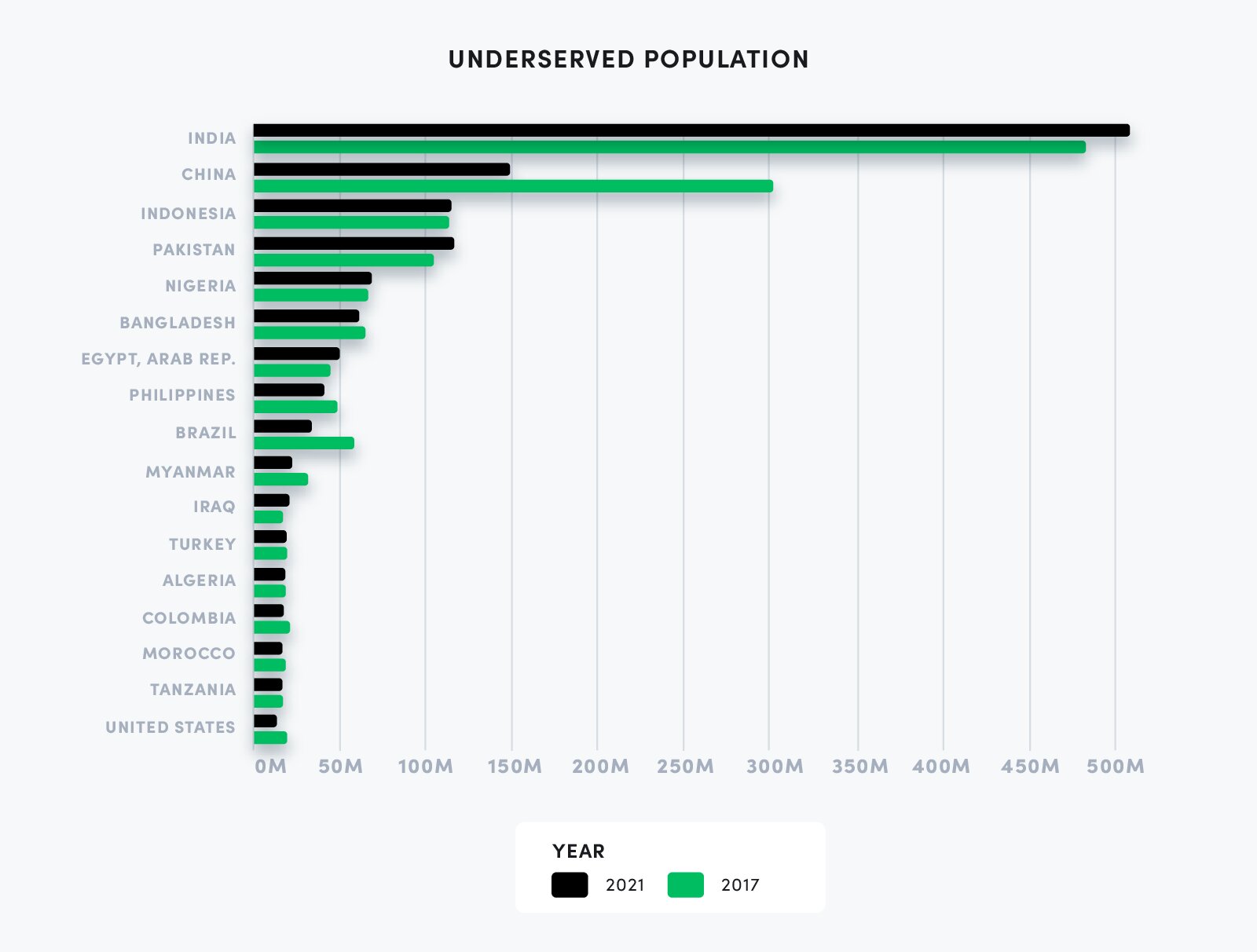

When country-level financial exclusion rates are combined with account inactivity levels, we see that many countries have still not made sufficient progress in financial inclusion. Ninety percent of adults in Afghanistan and 85 percent of adults in Iraq are unserved or underserved by the financial sector. Lebanon and Pakistan both have rates well above 80 percent. Egypt, which has been flagged for its fintech innovations and VC investments, still has 76 percent of adults not using financial services. The need for more inclusive financial services in these countries is higher than ever.

It is also important to consider that while the rate of exclusion and account inactivity are decreasing, the actual number of people in need of financial services is expanding in several countries due to population growth. Countries such as India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Egypt show a decreasing rate of exclusion and inactive accounts, but because of the fast-growing population, the actual number of people being left out of the financial system has increased since 2017.

4. New Metrics on Financial Worry and Financial Resilience Are a Welcome Addition

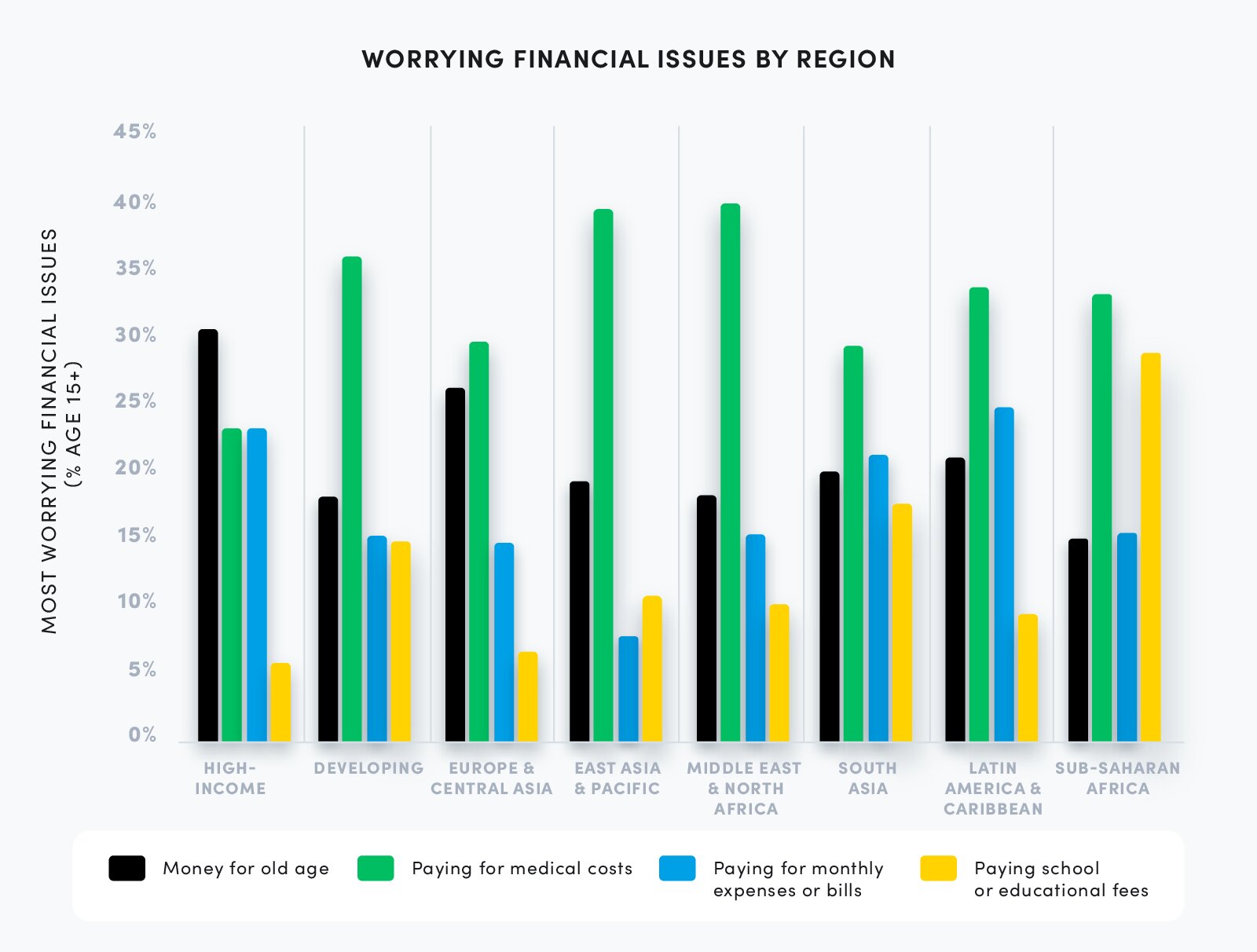

The new edition of the Global Findex database measures how worried adults are about financial expenses across four dimensions – medical costs, monthly expenses, school fees, and money for old age – and quantifies the number of worries adults have. As Leora Klapper discussed at the June 2022 RFF event, the share of adults in developing economies who are very worried about one or more financial expenses is double that of adults in high-income economies. Moreover, 22 percent of adults in developing economies worry about all four financial expenses, while this percentage is only 4 percent for high-income economies.

The cause for financial worries varies significantly between regions. The chart below shows that medical costs are the most common source of financial worry in developing economies – 36 percent compared to 23 percent in high-income economies. In Sub-Saharan Africa, education fees are a very common source of financial worry (29 percent) – almost twice the developing country average. In Latin America and The Caribbean, many households worry about paying monthly expenses (25 percent). In contrast, the most worrying financial issue in high-income economies is money for old age.

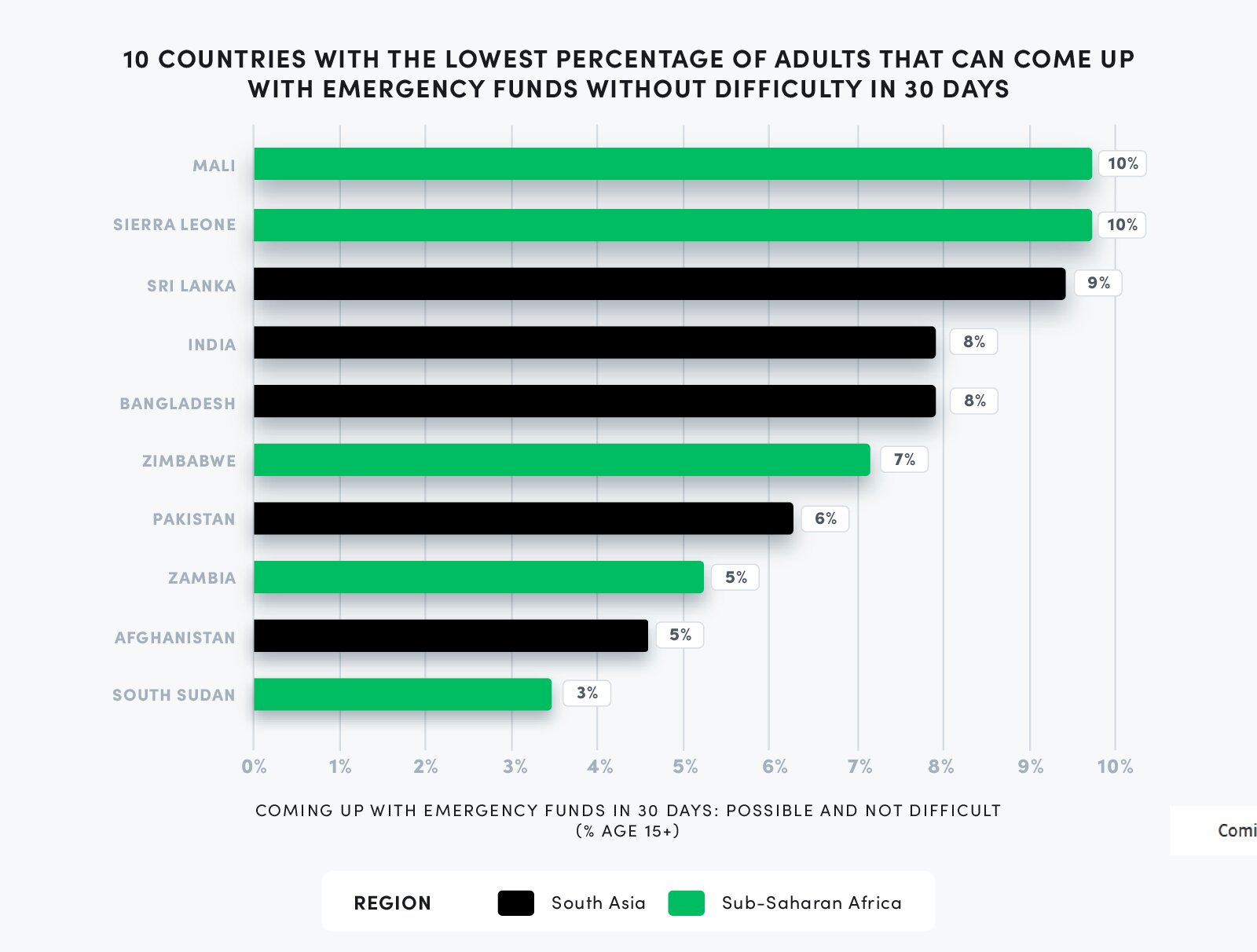

The 2021 Findex also points to a huge gap between developing and high-income economies with regards to financial resilience. While 79 percent of adults in high-income economies can access emergency funds within 30 days without much difficulty, this number is only 55 percent in developing economies. Five of the ten countries with the lowest percentage of adults who can easily come up with emergency funds are in Sub–Saharan Africa, revealing that the region still has significant work to do to build financial resilience.

Looking Ahead: How the Next Global Findex Can Help Us Rethink Financial Inclusion

The Global Findex team at the World Bank gets many requests to add new indicators and new questions to the next reporting cycle and they must make difficult decisions on which indicators to prioritize. In our view, to remain relevant, the Findex should expand in at least two main directions:

It is important to know if people feel over-indebted, if they must forego medical expenses or meals because of loan repayments, and if they turn to selling assets to repay a loan.

- Expand the list of indicators focused on financial consumer protection, particularly on over-indebtedness and fraud. There is a high demand, not just from researchers but also from regulators and practitioners, to have better visibility on specific consumer risks that impact consumer trust and well-being. Understanding the nature and gravity of these types of risks – especially over-indebtedness and fraud – is an absolute priority and the Findex can help to uncover how these risks manifest themselves within-country and across-countries. With the growing availability of digital credit and embedded finance solutions (for example, By Now Pay Later options), it is important to know if people feel over-indebted, if they must forego medical expenses or meals because of loan repayments, and if they turn to selling assets to repay a loan. Trust is also essential: increasingly, low-income consumers are relying on app-based financial services, which often have proved to be fraudulent or noncompliant with basic consumer protection regulations.

- Climate-related risks and coping mechanisms are a growing source of concern, which we need to start mapping. Financial inclusion has a growing mandate to help consumers address the risks posed by climate change. We still have limited understanding at the global and regional levels on the link between climate risk and the role of financial services in helping people adapt and respond to climate-related risks. CFI has developed a conceptual framework on Green Inclusive Finance that identifies four pathways for financial services to address climate risks: mitigation, resilience, adaptation and transition. Building new Findex metrics around these four dimensions would advance the inclusive finance community’s understanding not only about how climate risks affect consumers, but also about the coping mechanisms consumers employ as well as the gaps in current product offerings within the formal financial sector.