Hanh Nguyen is thrilled! Recently, an international organization introduced a new climate-smart seeder technology for rice production in his village. The seeder is less resource-intensive and will improve yields while allowing farmers to plant rice more quickly. While Hanh and the other men farmers in the village are celebrating their good fortune, his neighbor, Linh Bui — an agricultural laborer and single mother of four, is extremely worried. Cultural restrictions and childcare responsibilities restrict her from venturing out of the village seeking work, and she relies on the income she makes working in the rice fields. The new technology will reduce the need for wage laborers in rice transplanting, and Linh will no longer have an income. How will she now provide for her family?

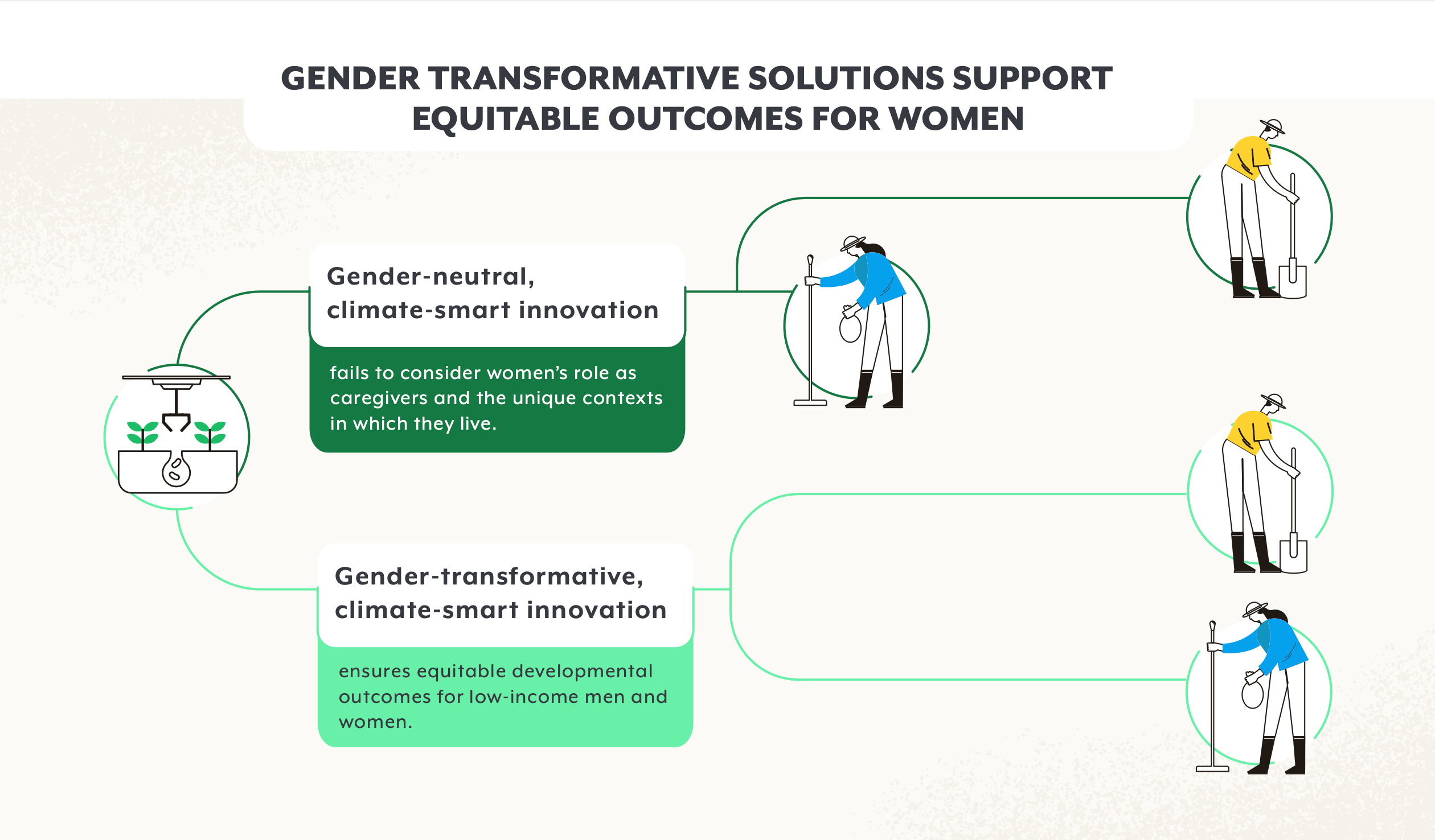

As the story above illustrates, development programs and processes often impact men and women differently. Social and cultural norms negatively impact women smallholder farmers, but there are numerous ways that organizations can design programs to work for both low-income men and women. Integrating norms-aware and norms-transformative approaches in climate and agriculture programs can shift existing power dynamics and ensure equitable developmental outcomes for low-income men and women.

We highlight innovative approaches that organizations are taking to address norms barriers, reach smallholder women, and provide them with information and capital – two critical impediments that prevent them from adopting climate-smart productive agricultural investments. Funders, policymakers, and providers can consider these insights as they invest in and design policies and solutions that integrate women smallholders in climate-smart agriculture.

Despite the Feminization of Agriculture, Norms Interfere with Women’s Adoption of Climate-Smart Agriculture

Evidence from the World Bank, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and others suggest that men and women experience the ramifications of climate change hazards differently due to their socially constructed roles and responsibilities. As Joanna Ledgerwood and Mayada El-Zoghbi pointed out in a recent blog post, gendered roles — and the underlying social norms that influence them — are the invisible guardrails dictating acceptable behavior, the division of labor, allocation of resources, and decisions about adopting new technologies, including climate-smart agricultural practices that can help low-income households build resilience against climate extremes.

Because of cultural and social norms, men and women smallholders have different roles and responsibilities, which in turn impact decisions related to agricultural investments and crop selection. For example, men typically prioritize cash crops for commercial gains, while women, who are likely to be subsistence farmers, tend to pay more attention to crop’s cooking time and potential for consumption, food security, and cattle feed. Furthermore, due to normative roles, women farmers tend to be the ones who consider potential water contamination risks from herbicides, as it is their responsibility to fetch freshwater (often needing to travel long distances to find safe water) and care for sick family members.

Women’s role in agriculture is significantly undervalued and women smallholders have limited access to land, assets, inputs, advisory services, and post-harvest technologies.

While these norms have been in place for years, increasingly, men are migrating for extended periods to seek off-farm opportunities and women are playing a larger role in both on-and off-farm activities. However, despite accounting for approximately 43 percent of agricultural labor in the developing world, women’s role in agriculture is significantly undervalued. Women smallholders have limited access to land, assets, inputs, advisory services, and post-harvest technologies. They are also less likely to be connected to commercial agribusiness supply chains. Gendered differences in awareness of the effects of climate change and adoption of climate-smart agriculture practices to mitigate such risks further leave women behind. According to FAO’s estimates, if men and women had equal access to productive resources, total agricultural productivity would rise by 20 to 30 percent and reduce global hunger by at least 12 to 17 percent.

Norms change is a complex and dynamic process that requires unlearning and relearning at the household, community, and national levels. To begin changing norms, programs must be designed with a gender lens. Solutions that focus only on access, delivery, or technological innovations – without explicitly accounting for the socio-economic and institutional contexts and gender disparities – can fail to achieve desired outcomes. For example, providing women with land tenure – often considered one of the biggest barriers for women smallholders – is insufficient by itself. Even if women smallholders are given property rights, they will need access to information, finance, markets, and decision-making powers to be able to leverage these rights into economic benefits. Even when women have property rights, traditional and cultural practices often require them to forfeit their rights to male relatives. Given these risks, women smallholders often lack the incentive to invest in improved climate-smart farming practices or commercially lucrative crops.

Gender-neutral or gender-blind solutions, such as the rice seeder example, often have unintended negative ramifications on the livelihoods of women like Linh because they fail to consider women’s role as caregivers and the unique contexts in which they live. So how do we address these norms barriers and support women smallholder farmers?

Delivering Training and Information to Reach Women Farmers

To begin with, we must focus on ensuring that women have equal access to information so they can make agricultural investments, access markets, and improve their wellbeing. Access to information is one of the biggest constraints women smallholders face. Traditional extension and advisory services often follow established practices that reinforce existing gender biases related to knowledge sharing and distribution of labor. Women smallholders with low literacy levels are therefore excluded from technical training covering seed variants, fertilizer use, feedstock, or new machinery and mechanized systems. On the rare occasion when women participate, they often need more time to learn and adapt because they are beginning from a lower baseline capability. This added cost of learning and adaptation can be a major deterrent that is often overlooked by development programs.

Access to information is one of the biggest constraints women smallholders face.

Furthermore, women face mobility restrictions and gender norms often dictate that women can’t attend male-led trainings in public spaces. Equipped with this understanding of gendered differences in mobility, information, and capabilities, under MEDA’s INNOVATE program, Krishi Utsho – a social enterprise operated by CARE Bangladesh – offered home-based training to rural women who were unable to participate in the programs conducted in the Krishi Utsho shops.

Additionally, while many organizations are leveraging smartphones to offer training, extension services, and real-time weather and price information at scale, women risk being left behind. Women are 8 percent less likely than men to own a phone (the gap is even larger for smartphone ownership) and 20 percent less likely to use mobile internet than men. Development organization programs such as Mercy Corps AgriFin (through its Sprout platform) and M-Shamba are trying to address this barrier through one-stop content platforms on feature phones that produce audio content that mimics the format of radio shows popular among rural women.

Recognizing that trust is key for adoption, Amplio involved rural women from North Ghana in the design of its Talking Book — a rugged, battery-powered device with pre-programmed infotainment content in local dialects that health and agricultural extension agents use to deliver information in hard-to-reach communities with limited electricity. Since the content is available offline, it is well-suited for women without a phone, allowing them to listen and learn together at their convenience and record their feedback. Amplio also collects usage statistics to understand user engagement and concerns and continually improve the content.

Embedding Norms Change Programming in the Delivery of Financial Services Can Improve Outcomes for Women

Group lending models promoted by the microfinance sector sought to address demand-side barriers women face, including mobility and collateral constraints. However, they failed to uproot the discriminatory gender norms at the source. As a result, low-income women became a vehicle for receiving and repaying loans with little or no control over their use. To get to the root causes of women’s exclusion, we must address the underlying power dynamics at the household and community level, and increase women’s control of resources.

Low-income women became a vehicle for receiving and repaying loans with little or no control over their use.

There are some promising approaches to embedding norms change programming to get to the root cause of women’s exclusion from the financial system. In Nepal, many men are migrating, leaving women in rural communities to fend for themselves. Under the prevailing social norms, women lack the knowledge, capabilities, or networks to partake in climate-smart agricultural investments, and their social networks are limited to include only other women with similar backgrounds. To address these barriers, International Development Enterprises (iDE) trained and engaged women community agents to help women-headed households access information and financial services that would enable them to invest in climate-smart technologies. These networks and agents were trusted intermediaries, allowing women and men in the community to support the initiative. The program offered bundled agricultural credit, insurance, and inputs to help women invest in climate-smart technologies.

In another case, Bidhaa Sasa, a last-mile finance and distribution company in Kenya, researched the household decision-making process, needs, and constraints of women smallholders. They learned that rural women in Kenya prioritized items that met their household needs and agricultural tools. Using these learnings, Bidhaa Sasa chose to leverage the group lending model to disseminate information and sell essential goods and agricultural innovations. Because top-performing women customers gave the product demonstrations, Bidhaa Sasa circumvented norms barriers and earned the trust of women smallholders.

These examples suggest that models that consider community and household dynamics and the needs and constraints of women smallholders during product design can increase relevancy and improve livelihood outcomes. However, more rigorous evaluations are needed to generate evidence on the long-term outcomes of these innovations.

Where We Go From Here

Unless we address the norms that limit women’s ability to benefit from the same tools and climate-smart agriculture practices that are available to men, women farmers will fall further behind. Norms-aware and norms-transformative approaches must be incorporated into climate-smart agriculture programs to ensure equitable developmental outcomes for low-income men and women. Stakeholder and gender analyses and customer research can shed light on local contexts and power structures, help us evaluate potential scenarios and tradeoffs, and support corrective measures to ensure that women and other marginalized segments are not harmed.

Unless we address the norms that limit women’s ability to benefit from the same tools and climate-smart agriculture practices that are available to men, women farmers will fall further behind.

Program designers, providers, and policymakers should critically examine who will be the direct user of the technology, who makes labor and resource allocation decisions, and who benefits from using the technology during the project conceptualization stage. And funders and researchers must support the testing of gender-transformative approaches in inclusive finance and incentivize providers to consider women and their contexts in the design and delivery of financial services. Only then will the inclusive finance sector live up to its promise of equitable outcomes for all.

For more background on existing literature, see CFI’s report Normative Constraints to Women’s Financial Inclusion: What We Know and What We Need to Know (2021).

Authors