Financial inclusion plays a strong role in a country’s economic and social development by reducing poverty, supporting sustainable and inclusive development, and enhancing shared prosperity. It is an enabler of 40 percent of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and is a useful measure of financial development. There is also ample empirical evidence tying financial inclusion with financially empowering behavior, including but not limited to a higher propensity to save.

Two recent surveys, the Karandaaz Financial Inclusion Survey 2022 (KFIS) in Pakistan and the Global Findex Survey (2021), and an examination of real-world examples provide some evidence that bank account ownership and access might be helpful in this regard. However, the overall impact of those indicators on improving people’s lives – especially women’s lives — appears to be nominal. Therefore, to help us understand the goals and principles of inclusive finance, we must reconsider which measurements are useful and appropriate for policymakers to use.

What really is Financial Inclusion? Measuring Usage over Access

There have been multiple definitions of financial inclusion over the years, but the underlying focus has been on the following key aspects:

- Access to financial services

- The degree of usage

- Quality of services

- Associated costs

These aspects are interrelated, but from a measurement perspective, regular usage of financial services and products should take precedence over account ownership because holding a bank account does not necessarily translate into regular usage. For example, after adjusting for inactive accounts, the percentage of globally banked individuals in 2021 decreased from 76 percent to 66 percent; in Pakistan, after adjusting for inactive accounts, the number of banked individuals in 2021 decreased from 21 percent to 13 percent according to the Global Findex. Data from KFIS in 2022 shows that 30 percent of banked individuals decreases to 27 percent after adjusting for inactive accounts. These discrepancies reflect the reality that access outpaces usage, which is not the desired outcome.

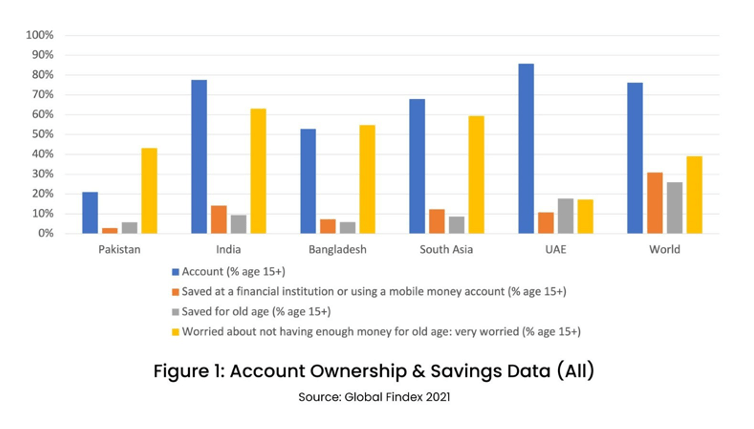

The data on savings as an indicator of consistent use of financial services and products also cements that the industry should not consider bank account ownership as the primary way of measuring holistic financial inclusion. However, around the world, countries and regions have prioritized bank account ownership in different ways. Figure 1 aptly depicts the outcome of these varying efforts. While a significant number of people own bank accounts, it appears that far fewer use them in ways that would offer direct benefits, such as savings.

Even in countries with higher levels of bank account ownership, like India and the UAE, only a fraction of these account owners saves money through a financial institution. In South Asia, where social safety nets are relatively weak, increasing the number of bank account owners does not seem to have much effect on people saving for their golden years — a meager average of 9 percent of the surveyed individuals saved for old age. Considering this data may explain why, on average, 60 percent of South Asians are ‘very worried’ about not having enough money for old age, according to the Global Findex. As indicated in KFIS 2022, data from Pakistan also depicts a similar pattern: only 16 percent of bank account holders and 10 percent of mobile money wallet holders saved money through their financial institutions.

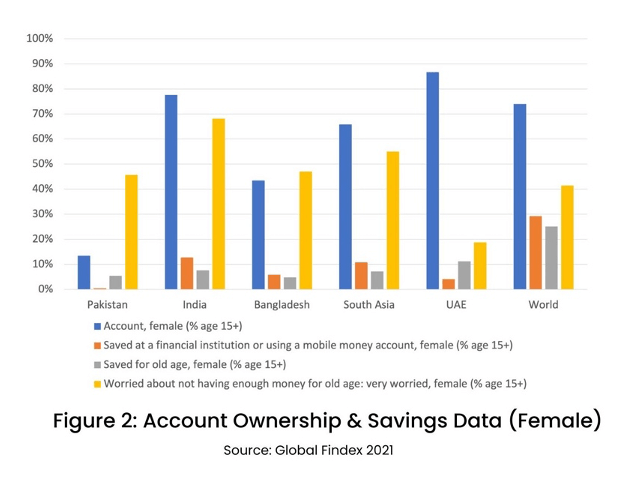

These numbers are more worrisome when we look at them from a gender financial inclusion gap perspective, as shown in Figure 2. Even in places like India, where women’s account ownership is as high as 78 percent, only 13 percent have saved at a financial institution or used a mobile money account. Furthermore, while only 8 percent saved for old age, 68 percent of women reported being ‘very worried’ about not having enough money for old age. With 13 percent account ownership in Pakistan, less than a half percent of women saved at a financial institution or used a mobile money account.

Involuntary Exclusion: a Better Target?

When data from KFIS 2022 shows that 81 percent of Pakistani adults are financially excluded (i.e., non-bank account holders), does that mean the policy agenda should include efforts to close this gap because more financial inclusion is necessarily better?

In a 2020 working paper published by IMF, “Financial Inclusion: What Have We Learned So Far? What Do We Have to Learn?,” authors Adolfo Barajas, Thorsten Beck, Mohammad Belhaj, and Sami Ben Naceur note that policymakers do not need to eliminate all the gaps because more financial inclusion is not necessarily better. The authors refer to the Financial Possibilities Frontier (FPF) as a framework to gauge an optimal level of financial inclusion in a country, given its structural conditions. As an illustration, there can be an instance of excessive financial inclusion, exemplified by the U.S. mortgage market before the subprime crises of 2008. Excessive financial inclusion is neither desirable nor sustainable in the long run. All households and firms do not need financial services, so it is paramount for policymakers to understand voluntary and involuntary financial exclusion factors.

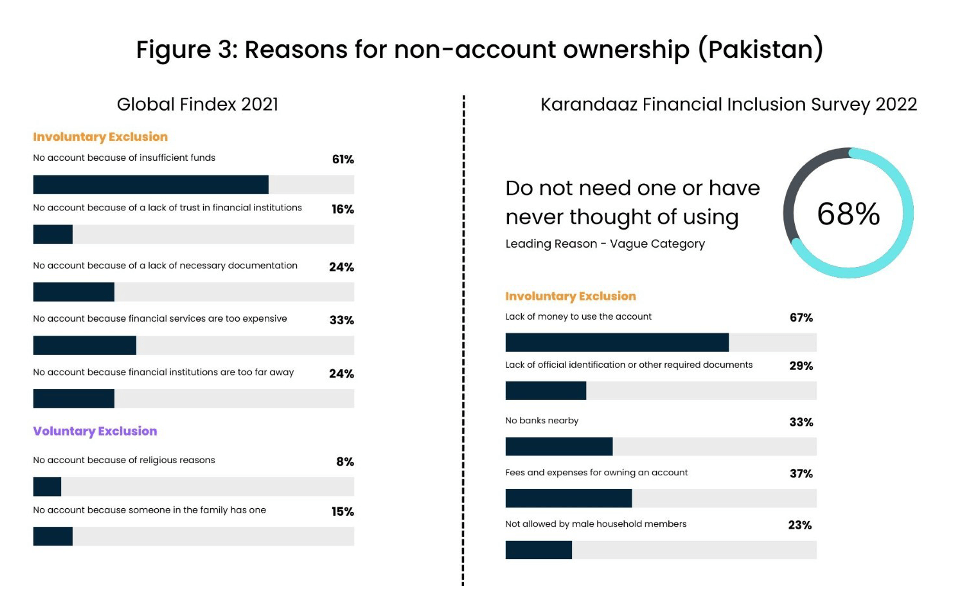

In the Global Findex 2021 survey, there were seven cited reasons by non-account holders for not having an account (Figure 3). One of the core reasons for voluntary financial exclusion is that someone else in the family has an account to access financial services. Even in countries where account ownership is significantly higher (i.e., 78 percent in India, 89 percent in Sri Lanka, and 86 percent in the UAE), one of the highest cited reasons by non-account holders was a family member having an account. In addition, not holding an account for religious reasons is another voluntary reason for financial exclusion. The other reasons cited for non-account ownership could be designated as involuntary reasons based on the minimum amount, cost, risk, and physical access.

Hence, as argued in the 2020 IMF working paper, there is a strong case for policymakers to target involuntary financial exclusion, which is driven by market frictions, instead of financial inclusion directly. However, even for involuntary exclusion, there is a clear argument for not targeting zero exclusion because some borrowers will always be too risky in the credit markets. Furthermore, based on the guidance from the FPF, specific individuals and firms would be excluded due to the high costs of provisioning financial services to them.

When financial inclusion is solely measured based on owning a bank account, the outcome does not truly reflect what it means to be financially included.

In Pakistan, the leading reason cited by non-account holders for not owning an account was that they “do not need one or have never thought of using one” (as shown in Figure 3). This explanation is vague at best and does not provide any opportunity to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary reasons. For example, some people might think they do not need a bank account because their family members already have one; others may have personal beliefs, such as religious beliefs, that make them not want to use a bank account. However, “not considering or thinking about” using a bank account can be addressed through financial education. Therefore, categorizing these individuals into one category does not offer any meaningful insight for policymakers or other stakeholders.

Moving forward, in light of the empirical evidence and literature, one can say that when financial inclusion is solely measured based on owning a bank account, the outcome does not truly reflect what it means to be financially included. Therefore, we need to adopt a more accurate measure of financial inclusion, especially in Pakistan. Involuntary financial exclusion may well prove a more useful guide for policy action. Otherwise, any positive change we celebrate would not hold much value because the actual effective increase in financial inclusion would remain relatively small.