CFI is focused on understanding how COVID-19 is impacting MSMEs and conducted a longitudinal survey to understand the scale of its impact. As part of CFI’s learning agenda on this topic, we welcome other perspectives and research on how COVID-19 impacted low-income entrepreneurs. This post shares research from Triple Jump’s assessment of how the pandemic affected borrowers, their businesses, and their capacity to service loans across five countries in Latin America and Southeast Asia.

Proponents of financial inclusion often argue that it boosts borrowers’ resilience, defined as “reducing the financial vulnerabilities of communities at risk,” notably by helping clients to build assets and gain access to credit. That theory was put to the test on a global scale during the COVID-19 pandemic, when lockdowns and changes in consumption patterns severely undermined the ability of many micro and small entrepreneurs to keep their businesses afloat.

Did financial inclusion really reduce entrepreneurs’ financial vulnerabilities in this context? To find out, Triple Jump and several partners conducted eight separate surveys of 1,638 microfinance borrowers across five countries in South America and Southeast Asia—Bolivia, Cambodia, Colombia, Myanmar, and Peru—during the second half of 2021, more than a year after the start of the pandemic. Analyzing the data from Triple Jump’s findings, three key lessons emerged.

Lesson #1: External Shocks Do Not Affect All Borrowers Equally

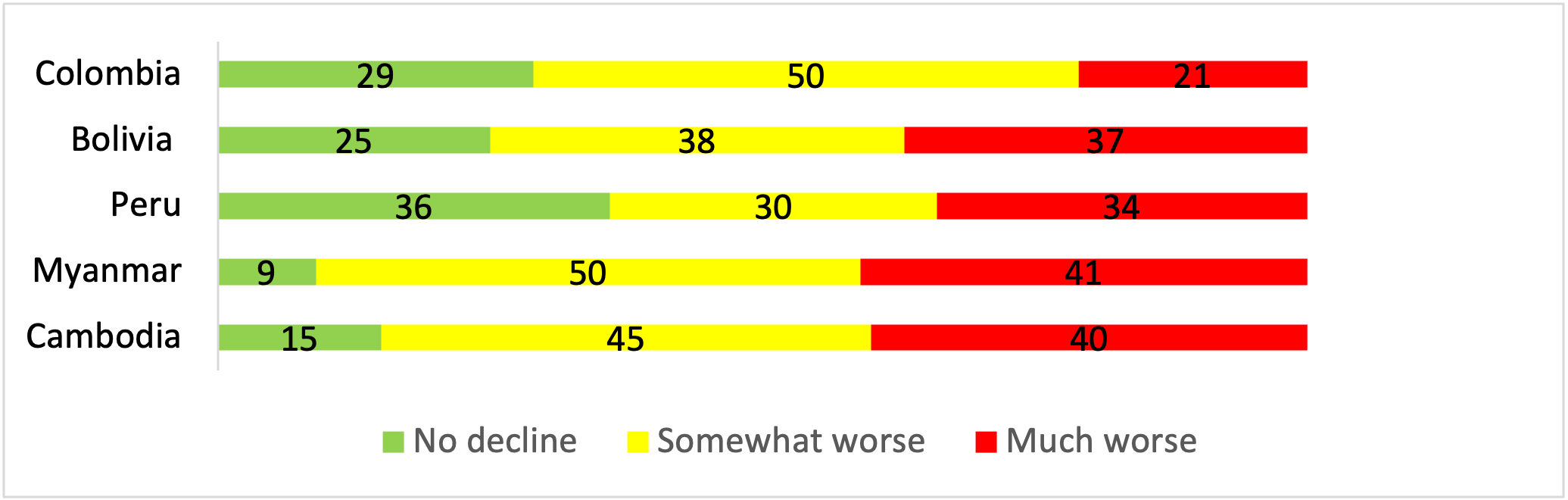

We found considerable differences between borrowers in terms of whether, and to what extent, they suffered financial shocks in the wake of the pandemic. In Peru, approximately one-third of borrowers reported that their financial situation had worsened significantly, another third had suffered a more moderate decline, and for the remaining third, the situation had not deteriorated at all.

Percentage of Borrowers Reporting Worsened Family Financial Situation

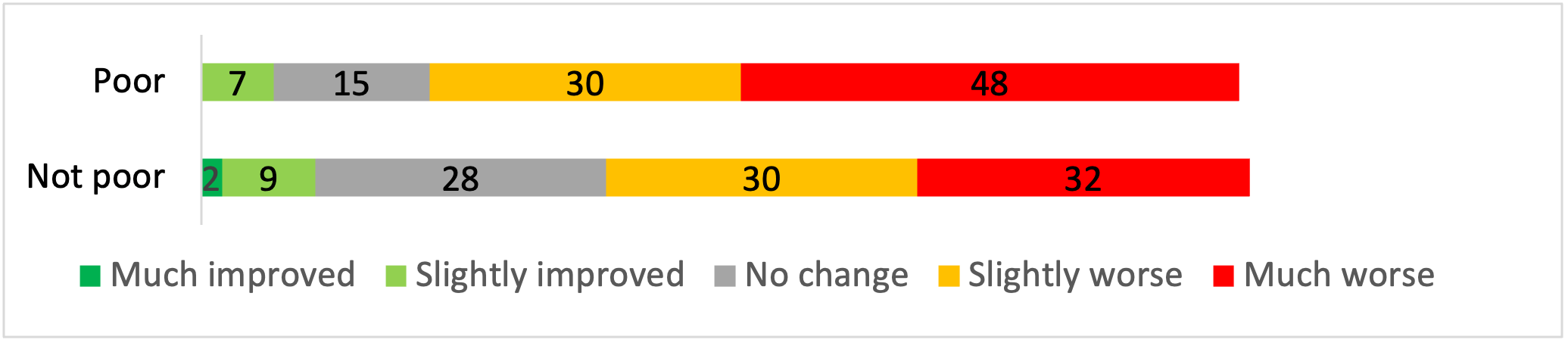

A closer look at the data revealed that borrowers whose families lived in poverty suffered a greater financial shock than those who were over the poverty line. Staying with the example of Peru, the financial situation of 78 percent of families below the poverty line declined even further in the wake of COVID, while this was true for 62 percent of families above it.

But again, there were significant differences at the household level, with a small minority of low-income clients even finding themselves in a slightly better financial position post-COVID than they had been before.

Changes in Family Financial Situation by Poverty Status in Peru

Thus, while it is true that, on average, some groups of borrowers will be worse affected by systemic shocks, lenders must bear in mind that the impacts on individual borrowers within any given group—even within especially hard-hit groups—may be very different.

Lesson #2: The Formal Sector Only Forms Part of the Larger Resilience Picture

Entrepreneurs in all five countries reported using a variety of coping strategies to respond to pandemic-related shocks. While some of those strategies involved formal sector lenders, most did not. When we looked at the data, three trends emerged.

First, drawing down savings and borrowing additional funds were only two among many coping strategies that respondents had employed. Other widely used coping strategies included reducing business stock, laying off employees, reducing business or household investments, selling and pawning assets, and cutting down on food consumption.

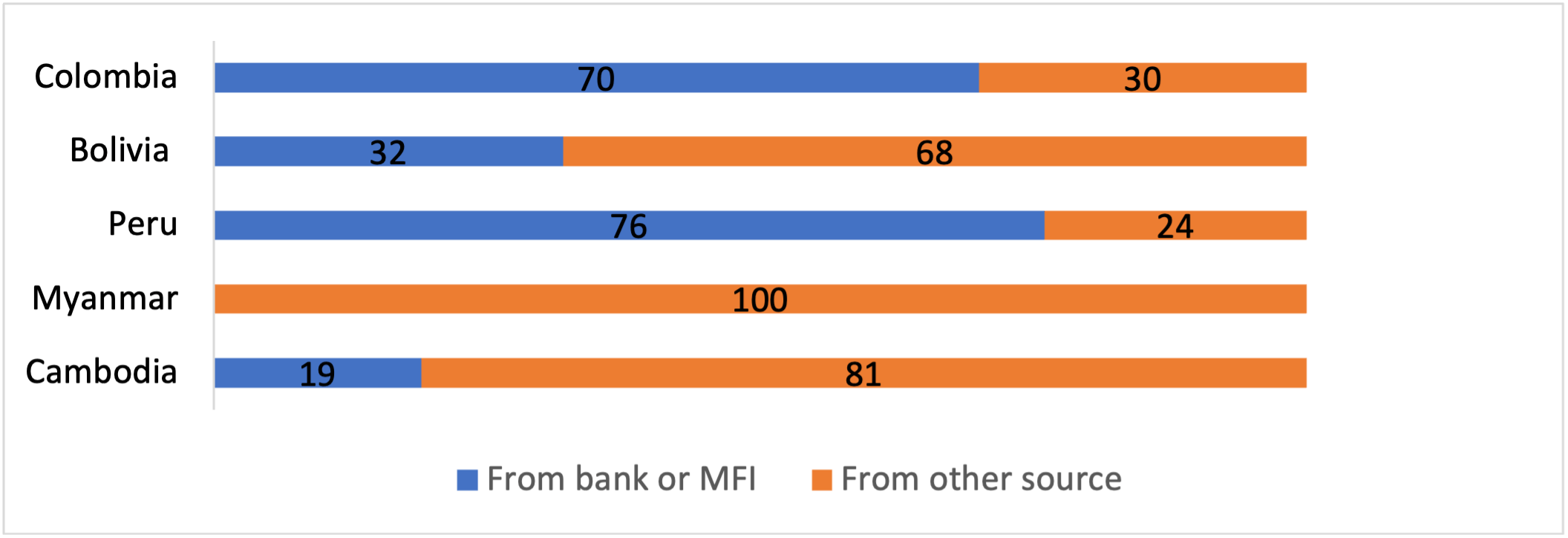

Second, most entrepreneurs across countries did not borrow additional funds from any source to help them weather the crisis. ‘Crisis borrowing’ was most frequently reported in Colombia with 56 percent of respondents having used the strategy. At the low-end of the spectrum, only 21 percent of Cambodian entrepreneurs had borrowed additional funds.

Third, when people did seek and secure a ‘crisis loan’, the role of banks and microfinance institutions varied widely between countries. In Peru and Colombia, around three-quarters of ‘crisis loans’ were provided by the formal sector, while in Bolivia, Cambodia, and Myanmar, informal sources of credit predominated.

Percentage of ‘Crisis Borrowers’ Who Borrowed from a Bank or MFI

Thus, while financial inclusion can, and often does, contribute to building resilience by allowing people to accumulate savings in times of plenty and access credit in times of crisis, entrepreneurs widely employ other strategies involving a diverse set of players to navigate crises.

Lesson #3: Need for a Nuanced Approach

Considering the above data, it appears that financial inclusion did indeed boost some borrowers’ resilience in the wake of the pandemic, and we found no indications that financial inclusion reduced the resilience of any borrowers. At the same time, many entrepreneurs chose to pursue alternative coping strategies that did not involve accessing formal financial services—ranging from reducing investments over seeking alternative or additional employment to cutting down on household consumption.

Thus, it appears that financial inclusion does boost borrowers’ resilience on average, but that this benefit is only sought and experienced by some borrowers. Future attempts to better understand the link between financial inclusion and resilience will need to focus on the individual business or household level.

This blog post is based on data collected for the report “Coping with long-lasting effects of the pandemic: How financial institutions supported borrowers affected by Covid,” published by Triple Jump in September 2022. The report is the result of a collaboration between Triple Jump, Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina (CAF), and the Responsible Inclusive Finance Facility for Southeast Asia (RIFF-SEA); the latter is managed by the Social Performance Task Force. The underlying surveys were executed by 60 Decibels. This article was commissioned by Triple Jump.