Topics

Key Takeaways

- It’s important for early-stage companies, especially innovative ones with exponential growth and market disruption potential, to be proactive about governance by ensuring a strong board is in place before periods of growth and important inflection points occur.

- Boards need to ensure investors are aligned on social mission and values.

- It’s important for the role of the board and the role of individual board members to be clearly defined and understood from the outset. This means that investor board members should be neither too involved in operations, nor merely fulfilling an obligation to have a board seat.

- The role of boards will evolve as a company grows and innovates, but strong, well-functioning boards add value at every stage of a company’s growth and development.

Board meetings should to be held at regular intervals, and attendees should “do their homework” and be prepared to actively participate. - Having a board provide “checks and balances” doesn’t necessarily mean slowing down growth or innovation. Strong boards challenge founders, make important introductions, partner in growth, and ultimately make a company more sustainable for the long term.

Goals of This Resource

For founders and leaders of innovative companies…

To raise awareness about the importance of strong governance structures early in the life of innovative companies serving base-of-the-pyramid clients.

For investors and independent board directors of innovative companies…

To set realistic governance expectations and standards in terms of the complexity and requirements they should have for boards at various stages in a company’s growth.

For the industry…

To serve as a key reference to help formulate these structures and best practices, and to align expectations.

What This Document Is

A guidance document: This document offers suggestions on how to form, manage and structure a board in an innovative company optimally.

A discussion starter: The quotes here are candid and may be disagreed upon–and that’s the point!

What This Document Isn’t

A be all and end all: Boards take on many forms and structures, and this document is not exhaustive in breadth or depth of company types or issues faced.

A magic bullet: This document does not offer one-size-fits all recommendations to overcome challenges.

Interviewees & Reviewers

We are extremely grateful to these individuals for their contributions and candid feedback on this resource.

- Lauren Cochran, Managing Director, Blue Haven Initiative

- David Dewez, Regional Director of Latin America and Caribbean, Incofin

- Tahira Dosani, Managing Director, Accion Venture Lab

- Andrew Goodwin, Managing Director, Mobisol

- Bill Harrington, Managing Director, Vista Ventures Social impact Fund

- Miguel Herrera, former Partner, Quona Capital

- Arvind Kodikal, Investment Officer, FMO

- Ethan Loufield, Director of Strategy, Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion

- Ivan Mbowa, CEO & Founder, Umati Capital

- Jacqueline Musiitwa, former Executive Director, Financial Sector Deepening Uganda

- Kwame Owusu-Boateng, CEO, Opportunity International Savings and Loans, Ghana

- Vikas Raj, Managing Director, Accion Venture Lab

- Prateek Shrivastava, Vice President, Digital, Global Advisory Solutions, Accion

- Martin Steindl, Manager, ESG, FMO

- Peter Stolze, COO, Lendahand

- Erik Vermeulen, Professor of Business and Financial Law, University of Tilburg

- Merima Zupcevic Buzadzic, Regional Corporate Governance Lead, International Finance Corporation

This work was conducted in partnership with FMO.

Background

The impact investing space continues to evolve to include new players, more digital channels, and increasingly innovative models. As the number of innovative, growth-stage companies serving the base of the pyramid increases, these companies – spanning a wide variety of growth stages—have tremendous potential to be revolutionary and disruptive. The structures and processes used to provide governance oversight to these innovative companies warrants further examination and special recommendations because there are specific issues—from regulatory matters to how often to schedule meetings—to consider with regard to innovative companies given their potential. Disruption and innovation notwithstanding, however, there will always be core governance “best practices” to guide all institutions, even if the role of a board evolves drastically over time.

The Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion (CFI) and FMO have partnered to develop a governance resource for early and growth-stage innovative companies. An innovative company is defined in this document as one that has a value proposition that has never previously been offered at scale or is wholly different from existing solutions and that supports the proliferation of inclusive finance. It may do so through direct product offerings of its own or through services provided to other companies in the market. This publication focuses on creating an awareness of the critical role of governance and urges a “call for action” for growth companies to focus earlier, rather than later, on building strong governance structures and practices than what is currently often the norm.

Why Focus on Governance for Innovative Companies?

It is particularly important to provide innovative companies with specific benchmarks and insights as they manage growth, since:

- Growth can happen quickly, and it is important to ensure that the proper controls and processes are in place before it occurs;

- Growth often requires additional capital and the need to attract new investors who may (and should!) want to see strong governance processes and procedures in place;

- Governance practices should be in-line with investor expectations throughout the life-cycle of a company;

- Aligning investor expectations can be particularly challenging for innovative companies that may need to pivot their business models quickly;

- Identifying the right moments to establish certain practices will avoid creating boards that are either too weak or too burdensome for the stage of the company;

- Governance improves transparency, particularly if there are strong founders in the business

- Governance instills a culture of best practices, even if a board is only partially implemented

All in all, corporate governance should be fit for purpose.

Interviewee“In a changing world, governance will continue to be key.”

Audience

- Founders/managers and board directors of early-stage/growth-stage fintechs and social organizations

- Development finance institution (DFI) professionals

- Donor organizations

- Shareholders and/or investors in start ups

- International development professionals—including staff at non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governmental and intergovernmental agencies— working to advance financial inclusion

- Academics

- Regulators

- Traditional financial service providers looking to serve base-of-pyramid organizations or clients

- Students and others with a general interest in social impact and financial inclusion

Methodology

Leveraging the networks of CFI and FMO, this learning tool incorporates the (sometimes divergent) perspectives of a wide variety of industry practitioners, including the following stakeholders: founders, angel investors, venture capital investors, board members, senior management and others—the focus always being innovative companies serving the base of the pyramid and making sustainable contributions to local economies and societies. The terms “board member” and “board director” are used interchangeably.

Through these testimonials, this resource demonstrate the importance of “getting the board right” from the start in order to survive and thrive. After an introductory discussion, we provide nine easily digestible and actionable principles.

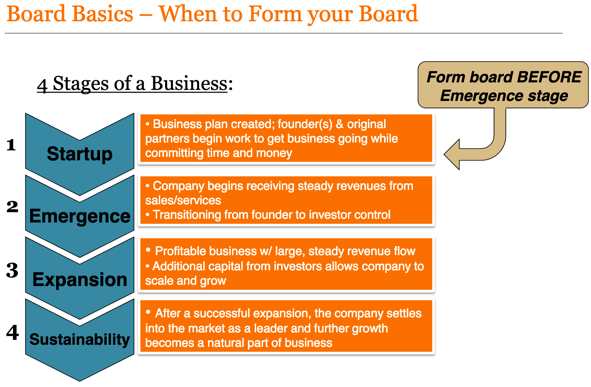

Stages of Company Growth

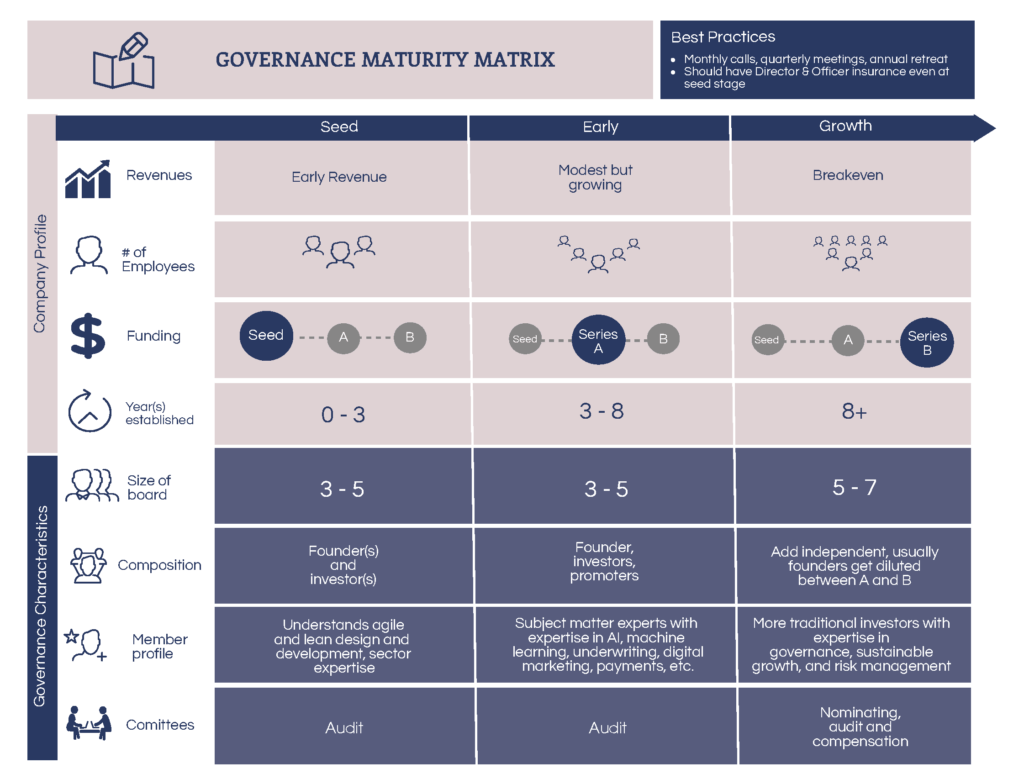

At this early stage, many companies need understanding of the basics of board management: how often to schedule meetings, what information to provide, taking useful minutes, being clear about follow-up actions, who will track what and, especially, who will find the bandwidth to get this done. Board management is typically not a pressing priority, though those who get basics in place will realize early value. Advisory boards can be formed at this stage as a “pre-board” (see Principle 2).

With investment comes greater attention to pulling together the elements of a functioning board. Most start with five members: two founding team members, two investors, and one independent director. Finding the right independent director is not easy particularly in markets where tech talent is thin. This is a common problem. Since the board that comes with investment is determined by factors such as capital provision or representing the founding team the challenge for innovative companies at this stage is assembling a board that best addresses the technical, regulatory and customer issues of a particular market.

After the second round of investment board priorities become more complicated by strategic issues. These issues include growth and new investment initiatives; considering potential partnerships; remuneration and compensation; retaining top talent, which can be exceptionally hard in some markets; financial tracking and planning; and fundraising. This is also when finding board members with specialty skills, such as a deep knowledge of local regulatory issues, becomes particularly important.

See also Annex 1: the Maturity Matrix.

Introduction

One of the main issues unique to innovative companies is that there appears to be a discrepancy amongst investors about the importance of governance processes and procedures. Some investors feel very strongly about ensuring solid governance principles are in place while others—both newer and veteran investors—seem to either take a “check the box” approach to governance, or place a lower value on board structure and governance principles and practices (and therefore do not ask for them).

Some innovative companies, because they are so attractive to investors, seem to be able to get away (almost right up to an initial public offering) with having informal governance structures, processes, and procedures. However, even the most successful innovative companies are questioned about corporate governance from a very early stage.

Innovative companies recognize the importance of having boards for advice and—more importantly, for very specific areas of expertise—but they don’t always see value in the formalization and structure of boards. To be sure, the priority for a company is to have a high-value investor who can give advice. However, part of what makes their value high is a strong commitment to governance oversight as a formal structure.

The following perspectives illustrate the differing and sometimes conflicting perspectives and experiences on governance:

- Entrepreneur Perspective: “We meet once a quarter to solicit feedback on board agendas, and have a once-a-month call on key performance indicators. We’re sharing. What more do you want from us?”

- Investor Perspective: “We may be less concerned now with a formal board structure—at least with the earlier stage companies—but my assessment of the willingness of the CEO to be transparent and to share both good and bad news on a regular basis is key. A negative assessment of that transparency is enough for me to pass on an otherwise strong investment.”

The director and board are discussing the same topic: governance expectations. But while the entrepreneur is focused on outputs (making sure he/she has checked off all the tasks on a to-do list), the investor is thinking about the outcomes of these actions, i.e., looking for signs as to how transparent the company is.

Interviewee“I believe in the soundness of good governance principles. Good governance principles are not going out of style or becoming a thing of the past. It may be more fluid but the principles are the same.”

Principle 1

Board members should be required to show up prepared and engage with the work.

Boards should be formalized as early as possible in the life of the organization. But this doesn’t mean having a board just to have one. It means scheduling, sticking to and carrying out fruitful, productive meetings. Founders and directors alike are very busy, and meetings tend to be postponed repeatedly. Formalizing board meetings and having a clear agenda will keep everyone on task and engaged. The board directs and guides the management of innovative companies, so this keeps entrepreneurs on the right track and focused on agreed upon plans and priorities.

Just as a good student studies copiously prior to class, board members ought to spend at least two hours preparing for each hour of a board meeting. And like a good participatory student, a board member of an early-stage company should be able to actively participate and guide the entrepreneurs during the meeting. Examples of this “in class” support are prioritizing efforts, challenging assumptions and keeping entrepreneurs focused by setting adequate key performance indicators (KPIs). Board members should always stand ready to take on assignments and see them through without constantly having to be reminded. And—not to belabor the analogy—just as a teacher prepares a syllabus at the beginning of the course, the company should also put together a board package of meeting schedules, financial information, strategic planning documents—and whatever other information deemed crucial—to help prepare incoming board directors.

Lastly, entrepreneurs might have blind spots, and their passion can lead to dominating meetings. Engaged board members can provide meaningful and valuable advice, but they cannot do so if they are absent or continuously checking their phones during meetings.

See Annex 3 for more information on structuring board meetings and setting expectations of directors.

TIP:

Follow the “three strikes, you’re out” rule if you must postpone meetings. Two is the maximum amount of times you can put off a meeting without seeming disinterested or unprofessional.

Interviewee“For such small companies, I would think that a one-hour conference call on a monthly basis with the two or three directors, in lieu of a formal board meeting, would be sufficient and set a good precedent. But I am reminded that every director should expect to spend two or more hours in preparation for each hour of a board meeting.”

Principle 2

Understand that early-stage company boards are different from mature company boards.

Entrepreneurs are dedicated to their ideas and do their utmost to make the business a success. More often than not, establishing basic corporate governance structures is not at the top of their agenda. It might be perceived as a burden, and its value to the company is not always fully understood. A well-established board that is fit for purpose given the development stage of the company is, however, instrumental for the success of the company.

Roles are different when a company becomes more established. In more mature companies, the board traditionally has an oversight role with a strong focus on strategy, financials and internal controls.

The role of the board for early-stage companies is fundamentally different from that of more mature companies: it should not be a burden that prevents a company from being able to innovate, grow, or be agile. Entrepreneurs should not be bothered too much with detailed minutes, detailed board packs and preparing lengthy memos. Thus, the board should be able to challenge and guide entrepreneurs, as well as fill gaps to support them (e.g., network or business development). As the company grows, the board will play more of an oversight role suitable for an institution that is well-established. That said, new boards should still implement at least financial oversight and transparency to the same extent as mature boards.

Advisory boards can be useful when founders are still not sure if they are ready to form an official board and want to get a sense of how it would be to have a group of outsiders provide additional input on strategy in particular. This applies to founders who didn’t receive investor funding that came with a right to appoint a director. An advisory board, however, should not be a long-term governance structure.

Interviewee“Those innovative companies getting away with not having more formalized governance at the B and C-levels are able to do so because they are rock stars and investors are beating down the doors because they are such valuable investments.”

Principle 3

Expectations of board members should be clear from the beginning.

An investor adds value directly through their investment in the company, and company founders want investors to support their vision. But an investor often expects to add value in other ways to ensure growth and profits. What often happens, however, is that expectations on both sides are not clearly communicated early, leading to frustration from all parties. Communicating expectations from the outset helps established board members think through expectations, and helps convey those expectations to potential new board members. It also provides honest, realistic expectations for onboarding once they agree to join.

Expectation-setting doesn’t mean putting in place heavy reporting requirements or complex committee structures, but it does mean clarifying roles and establishing parameters for constructive discussion and decision making, such as Robert’s Rules of Order. These parameters can take the form of a committee or an advisory board to talk through challenges.

A value-add investor at this stage understands that the business will pivot often and will demand agility from other investors and founders alike. On the other hand, investors want to know that the CEO and his/her team are willing to communicate clearly and “share the dirty laundry.”

Interviewee“I don’t have the liberty of making mistakes and learning because there is a heavy set of eyes watching.”

Principle 4

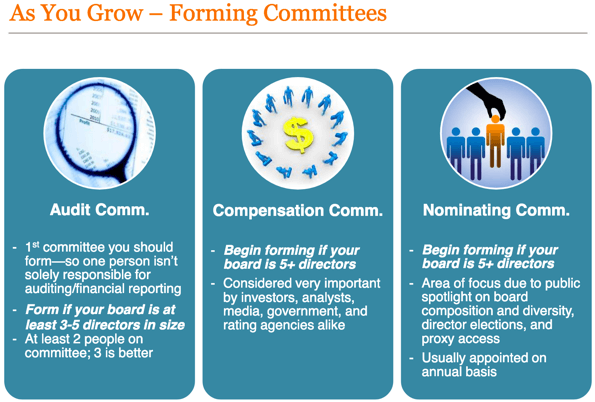

Having organized board committees too early is not recommended, but thinking about future committees is.

At mature companies, it’s typically the board committees that are the workhorses of the board. Assigning specific tasks to a board committee and discussing specific topics in a smaller group can make the board more efficient. This is particularly true with larger boards, where it is neither efficient nor effective to discuss all agenda items with the full board. Once the board grows, it’s important to consider establishing committees to improve board effectiveness. This is typically the case once the board has more than five members.

Early-stage companies typically have small(er) boards, and committees may not be warranted yet because it makes board structures unnecessarily complex. Rather, an important value of boards in early-stage companies should be in the diversity of views and support for agile decision-making and action. Subject matter experts tend to cluster in committees (i.e., financial service professionals in the audit committee) where out-of-the-box views may be given more consideration.

In more regulated industries (e.g., financial services), on the other hand, there might be a requirement to have specific board committees (e.g. audit committee). In those cases, a company has no choice but to comply, especially where the size and reach of a company is not considered in regulations.

TIP:

Management should think about specific board committees for when the company matures and communicate this to the board. It shows investors you are organized and have thought through governance structures. See Annex 3 for more on committees.

Principle 5

Having the right kind of experience on the board is key.

Board members should bring skills and experiences that support and complement the management team. Entrepreneurs might have brilliant ideas, but lack the required network or business development skills, and may have a limited knowledge of the expectations of (future) investors. Board members should bring missing skills and experiences to the table that are instrumental to the longer-term success of the company. Board members typically add value by facilitating future capital rounds, opening up access to a network and bringing expertise in business development.

At the growth stage, “scalers” are one type of desired board member. Scalers are investors who may not be subject matter experts but have experience scaling a company and thinking and acting strategically. Their modus operandi is “we can get you through series A and B with our connections.” Another value-add board member is someone based in a served market, because he/she understands intimately the company’s operating environment, including political and regulatory challenges.

Principle 6

Board members should have a passion for impact and be aligned with company values.

Any company serving vulnerable populations at the base of the pyramid must be particularly focused on the impact of their products and services—both positive and negative. As with any company, having a deep understanding of your clients and designing client-centric products and services makes sound business sense.

However, some investors do “check the box” due-diligence and don’t ask detailed questions about actual social impact. To counteract this, a strong governance structure can help to ensure:

- a sense of social alignment among investors,

- the social mission is truly embedded into the company’s practices,

- the impact being measured is tailored specifically to the company,

- the company doesn’t drift from its core social mission as it grows.

Interviewee“If you figure out a system where you can gather lean insights, pull it together in a way that tells a really coherent story, and allows your board to be able to engage with that story over time, that empowers the board to be able to better support you.”

Principle 7

Push back when necessary.

Many innovative companies are dominated by one or two very strong individuals with a very clear vision. Sometimes, boards run the risk of that vision dominating everything. If there are not enough people pushing back or challenging governance perspectives, things can turn into a dictatorship —and future investors do not want that. This is not to say that a board should always put up roadblocks and slow things down, because innovative companies need to be nimble, but the board must not be afraid to challenge ideas or perceived realities of a founder.

As one interviewee put it: “The board is the biggest bane and not adding value—on both sides. They were too close. The investor needs to realize that their hand-holding is for them and not helping the innovative company.”

Likewise, founders and entrepreneurs should not be afraid to receive criticism. When blood, sweat and tears are spilled leading an innovative company, it’s easy to resent criticism or dismiss it as ill-informed. It’s nothing personal. The director has the company’s best interests in mind—otherwise she/he wouldn’t be there!

For more on the role of boards in challenging management, watch CFI’s “Governance for Startups.” See Annex 2.

Interviewee“It felt like betrayal, but ultimately, I saw a union of thinking from a united board. That made me realize that I was standing on the wrong side of the bridge. Since the pivot, business has grown significantly. It’s hard to admit it, but the board forced that change. I would not have gotten here any time soon if left to my own devices.”

Principle 8

Have a concrete plan and timeline for the evolution of governance structures and roles.

Like all companies, it is important that the corporate governance structures of an early-stage company are fit for purpose. The structures should reflect the ownership model, size, complexity and risk profile of the company. Those structures should mature as a company grows, and this is particularly the case for fast growing companies.

As institutions mature, their boards gradually formalize functions previously executed informally. Examples of this include creating committees of the board to undertake detailed work in support of board decisions, developing a board manual, or formalizing the CEO’s annual review process. Over time, a board of an early-stage company, when successful, will develop into a mature board. It is difficult to generalize about what acceptable governance looks like at different stages, but organizations should continuously assess if their governance structures are fit for purpose. Also, companies need to recognize the need to further professionalize the corporate governance structures as the company matures.

The Maturity Matrix (Annex 1) provides a view on a board maturity model. It is important for a company to recognize that it should think about its board sooner rather than later. A fit-for-purpose board is a strong asset to the company, and the lack of an appropriate governance structure is a real liability.

Principle 9

Add an independent board member(s) as the company grows.

The initial board of a company is usually comprised of the founders and one or two early investors. This board is typically the first formalized corporate body that performs work that was previously carried out informally.

The board will grow once more investors come onboard as additional funding rounds are completed. The founders typically only have a single seat after series A, with the investors taking the other seats. A board will become more professional as it matures, which would typically be the moment where a first independent board member comes in. The independent board member is best positioned to act exclusively in the best interest of the company and should be a driving force behind further professionalization of board practices.

Final Thought

“From a governance point of view, you simply have to do what is right, right from the start, rather than wait until much later. Sometimes, for startups, they tend to think that getting the governance structure right is expensive, that it takes too much time, but I think that it’s worth their while to make sure they get it right.”

Interviewee“In the development of companies, the board role changes to a more oversight role in those cases where an institution is well established.”

Annex 2

VIDEO

“Governance for Start Ups”

From: Africa Board Fellowship Roundtable: Governing in a Digital World. Addis Ababa, 2017.

Published by the Center for Financial Inclusion at Accion, January 2018.

This video offers additional points for executives and board members to consider:

- Engage with regulators. Working closely with regulators to understand parameters, while at the same time pushing boundaries, is a delicate balancing act, but one that can pay dividends. Taboos and stigmas about how things are done should be challenged in a way that’s constructive, while for their part, regulators should eagerly embrace digital transformations.

- Ensure board diversity and independence. With many young fintechs dominated by one or two people with strong visions for the future of financial inclusion, it’s imperative that board members push back and challenge founders in the right way and implement checks and balances – all while keeping ensuring nimble action. These professionals should have access and experience in emerging markets. This can give tech-oriented executives a chance to step out of the “echo chamber” and provide real time feedback for what the business climate is like, who they should get to know, and how to make solutions culturally relevant.

- Consider partnership potential. Innovative startups should understand what incumbent businesses are doing and the gaps in their business models in order to find opportunities to collaborate. Figure out what’s core and non-core in a business model and partner with other businesses in those non-core areas. It’s also helpful to determine imperatives for success in partnerships after determining where they can be forged.

Video Interviewees

- Rohit Acharya, Co-Founder and Chief Data Scientist, First Access

- David Cracknell, Global Technical Director, MicroSave

- Buhle Goslar, Director of Customer Intelligence, JUMO

- Kelvin Kizito Kiyingi, Deputy Director of Communications, Bank of Uganda

- Paul Lamont, Director, Digital Services, Africa, Accion

- Patrice Nkhono, Board Director, FDH Bank

- Emil Sjoblom, Chief Commercial Officer, BelCash

Watch Video

Watch “Governance for Start Ups”

Annex 3

SLIDE PRESENTATION

Best Board Practices for Startups/Seed-Stage Businesses

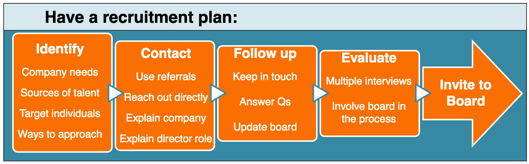

Created by Accion Venture Lab, a seed stage investment initiative, this resource also offers early-stage businesses helpful content to guide creating and leveraging a board, structuring committees, recruiting new members, and more. It also provides more detail on board meetings, including tips for creating agendas, what items to include in a board deck, how to take minutes, and so on. “Best Board Practices” is divided into three parts:

- Building & Structuring Your Board

- Leveraging Your Board

- Board Meetings

Link to the Presentation: https://www.accion.org/best-practices-for-building-and-leveraging-a-startup-board

Select slide graphics: