Results from CFI’s second wave survey of the economic impact of COVID-19 on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) are cause for cautious optimism, showing MSMEs are generally on an upward trajectory after weathering the initial economic devastation caused by the pandemic. While these indicators of recovery are promising, there are several signs that MSMEs, and their owners’ households, are vulnerable to another economic downturn. Given the volatility caused by COVID-19, what can policymakers and financial service providers (FSPs) do to bolster the recovery and decrease vulnerability?

Businesses Are Opening, Profit Levels Are Stabilizing, and Hiring Has Increased Dramatically

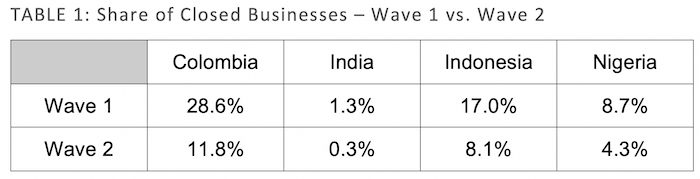

In the first wave, 15 percent of MSME owners reported their business closed at the beginning of the pandemic. As I wrote in CFI’s brief examining that data, most of these closures were the result of government restrictions on movement in response to the public health crisis, but by the time CFI completed its first set of surveys, governments in three of the four countries (Colombia, India, and Nigeria) had recently or were planning on loosening restrictions. Thus, it may be of little surprise to see that large shares of respondents with a closed business in wave 1 reported they were operating in wave 2. The declines in closures in each market were dramatic, falling by at least 50 percent.

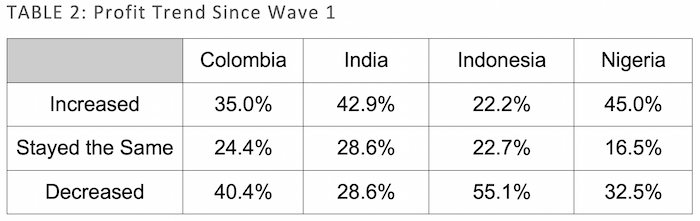

As the business climate improved, so did MSMEs’ earnings. In the first wave, 83 percent of respondents reported their profits declined — a staggering figure which was indicative of the liquidity challenges respondents were facing. Those declines have bottomed out for most respondents. In every market other than Indonesia, the share of businesses with profits that have stayed the same or increased was larger than the share of businesses with profits on the decline.

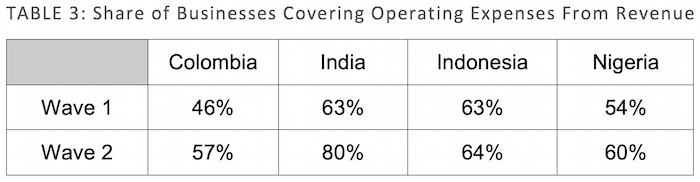

There is evidence that the improvement in profit trends had a positive impact on business operations. As shown in Table 3, the share of owners reporting they could cover their expenses from operating revenue increased in each market, although those gains were not significant in Indonesia. In addition, there has been an expansive increase in the number of people MSMEs employed in Colombia, India, and Nigeria. Employment surged by 66 percent in Colombia and 42 percent in Nigeria relative to wave 1. In India, employment nearly doubled and was higher in wave 2 than it was at its pre-pandemic peak.

But MSME Recovery, Household Resilience Are Vulnerable

This data is encouraging but there are still several indicators highlighting the fragility of the recovery. For instance, while it is positive that many businesses have re-opened, most of those are new businesses that entrepreneurs started as opposed to closed businesses that re-opened once pandemic restrictions were lifted. While the number of businesses in this scenario is too small for robust quantitative analysis, there are indications that these businesses are in a more precarious financial position than their peers that never closed. For example, in Colombia, new business owners reported spending down more of their savings (80 percent) compared to owners who never closed (70 percent). Meanwhile, the number and value of outstanding loans were similar in both groups. Similar patterns can be seen in Nigeria, too. Meanwhile, the improvement in profit trends is promising, but as Table 2 shows, there was a large minority of respondents — and a majority in Indonesia — who reported their profits were still on the decline.

There are indicators that MSMEs’ recovery — and the resilience of respondents’ households — is vulnerable to another economic downturn.

This fragility extends to MSME owners’ households: the data shows that there were no consistent improvements in household resilience. Colombia, India, and Indonesia all displayed similar patterns defined by meager, if any, changes in the share of respondents reporting their households could cover essential expenses, the duration for which they could continue doing so given no income, and levels of food security. Nigeria showed the most expansive improvement in household resilience relative to wave 1, with more respondents reporting their households could cover their essential expenses and that they could do so for longer if they lost all their income. However, food security — even after a decline — remained persistently high. Twenty-five percent of respondents reported they or someone in their household had gone to bed hungry since wave 1 because there was not enough money for food. And while there is some evidence that financial flows are increasing, households’ best buffer against an economic shock, savings, has largely been exhausted.

Policymakers Should Provide Direct Assistance, Regulators Should Continue Prudential Flexibility

In CFI’s brief examining the first wave of survey data, I discussed how most MSMEs in our survey were not recipients of direct assistance despite major expansions of social assistance programs in each survey market. That was also true in the second wave of survey data. The only country where respondents reported a significant difference in receiving public support was India. Levels of support remained limited and unchanged in the other markets.

For MSMEs in low-income countries, this appears to be a widespread issue with the World Bank reporting that only 10 percent of businesses in low-income markets said they received some sort of public support. They also noted how the probability of receiving policy support was substantially lower for smaller firms, which comprise the majority of CFI’s sample, compared to larger firms.

To ensure the recovery continues, policymakers should provide direct assistance to MSMEs and regulators should continue affording prudential flexibility to FSPs.

Collectively, this data continues to support the need for expanded support measures that are structured to provide immediate relief to MSMEs. They also provide additional guidance on potential ways to design programs to be most impactful. For instance, efforts aimed at maintaining or boosting employment are less likely to have a major impact given the gains seen in wave 2. However, there appears to be a need to support MSME owners who have closed one business because of the pandemic and are now starting another. As this data suggests, this group is particularly vulnerable, so direct assistance that helps them improve their financial position (by providing grants, lower-cost debt, or other measures) would be particularly beneficial.

In addition to an expansion of direct assistance programs, I also wrote about the need in the medium-term for FSPs, especially lenders, to adapt their products and services to support MSMEs’ liquidity. Since then, CFI released a policy brief which explored, among other topics, how flexibility of prudential regulations could serve as a powerful tool to help FSPs and their clients cope during the pandemic. With the ability to offer moratoria, pardon interest, and offer other restructuring, FSPs can meaningfully support the liquidity needs of their customers. Denise Dias, the author of the policy brief, notes that regulatory flexibility, which many regulators have adopted in response to COVID-19, allows FSPs to provide relief to borrowers without needing to automatically reclassify the loans as higher risk, which in turn preserves FSPs’ liquidity and supports their short-term viability.

There is ample evidence to suggest there is value in extending this flexibility into the future as many respondents’ ability to fulfill their debt obligations remains constrained by persistently lower earnings, declining profits, and an ability to cover operating expenses from revenue alone. It is, however, important to note that this is not a blanket approach and regulators need to evaluate the circumstances in their markets carefully. In Indonesia, for example, continued flexibility appears especially important as respondents in that market underperformed in the recovery relative to their peers. In India, however, additional regulatory flexibility appears less necessary as MSMEs there have generally been performing well.